Bilingual belt

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The bilingual belt (French: la ceinture bilingue) is a term for the portion of Canada where both French and English are regularly spoken. The term was coined by Richard Joy in his 1967 book Languages in Conflict, where he wrote, "The language boundaries in Canada are hardening, with the consequent elimination of minorities everywhere except within a relatively narrow bilingual belt."[1]

Joy's analysis of the 1961 census caused him to conclude:

The pattern so common during the 19th Century, of English- and French-speaking communities intermingled within the same geographical region, is now found only along the borders of Quebec Province, within a zone of transition separating French Canada from the English-speaking continent. This 'Bilingual Belt' includes Northern Ontario, the Ottawa Valley, Montreal, the Eastern Townships of Quebec and the northern counties of New Brunswick.[2]

Overview[edit]

The bilingual belt is the frontier zone on either side of what Joy referred to as "Interior Quebec"—the heartland of the French language in North America, in which, in the 1961 census, over 95% of the population gave French as their mother tongue and 2% speak only English.[3] The bilingual belt is, therefore, the "region of contact"[4] between the Quebec heartland in which French is the overwhelmingly predominant language and the rest of Canada, in which English is the overwhelmingly predominant language.

When the bilingual belt is added to the French language heartland of "Interior Quebec", the result is:

an area 1,000 miles long, bounded on the West by a line drawn from Sault Ste. Marie through Ottawa to Cornwall and on the East by a line from Edmonston to Moncton....[O]ver 90% of all Canadians who claimed to have a knowledge of the French language were found within the Soo-Moncton limits. Outside this area, not one person in twenty could speak French, and not one in forty would use it as the language of the home.[5]

Joy recognized the continued (although diminished) existence of residual French-speaking communities in places like Yarmouth, Nova Scotia and Saint Boniface, Manitoba, but these communities were isolated and very small, and were, in his view, already well on the way to extinction, along with most of the smaller pockets of English-speakers within Quebec. For example, he had this to say about the French language in Manitoba: "The Franco-Manitobans have resisted assimilation more effectively than have the minorities in the other Western Provinces, but the 1961 Census reported only 6,341 children of French mother tongue, as against 12,337 of French origin. This could well indicate that the actual numbers, and not merely the relative strength, of those who retain the old language will soon start to fall."[6]

Regions within the bilingual belt[edit]

Strictly speaking, the bilingual belt has never been a single contiguous region. Instead, the parts of the bilingual belt lying within Ontario and west Quebec form one geographical unit, and the part in northern New Brunswick formed a separate geographical unit. Joy also noted that there was considerable demographic variation within the bilingual belt itself, based on such factors as proximity to the unilingual French-speaking heartland of "Interior Quebec" and the ratio in any particular part of the bilingual belt of native French-speakers to native English-speakers. He summarized these regional divisions as follows:

- In New Brunswick

- In seven counties[7] in the province's north and north-east, French was the mother tongue of 59% of the population. Joy indicated that in this region, rates of bilingualism were high among francophones but that French "is spoken by practically none" of the Anglophones in this part of the bilingual belt.

- In Quebec

- Joy pointed to a strip of territory running from the Eastern Townships westward through Montreal to Pontiac County.[8] In this region, French was the mother tongue of 70% of the population, and English of the remaining 30%. The rates of bilingualism were 40% for persons with French as their mother tongue, and "less than a third" for persons with English as their mother tongue.

- In Ontario

- This part of the bilingual belt consisted of "the eleven counties which form a band, along the Quebec border, running from the St. Lawrence River to the Upper Lakes".[9] Joy reported that in this region, French was the mother tongue of 30% of the population, and that fewer than one quarter of persons of French descent had been assimilated.

Demographic trends in more recent years[edit]

Demographic data from more recent censuses indicate that the geographic extent of the bilingual belt has remained largely unchanged in the nearly half century since the 1961 census, although assimilation and migration patterns have caused some population characteristics to change over time. Most notably, rates of bilingualism among the English-mother tongue population in the Quebec part of the bilingual belt are now far higher than they were in 1961.

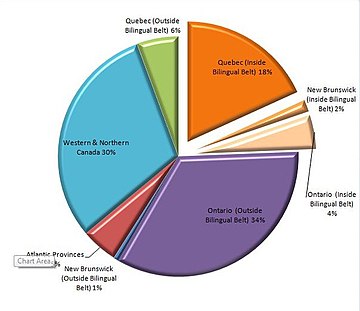

Based on the 2011 census data, 85.7% of Canadians with knowledge of both official languages live within Quebec, Ontario and New Brunswick, the three provinces which comprise Canada's bilingual belt.[10][11][12] Only 14% of Canadians with knowledge of both official languages live outside of those three provinces.

The bilingual belt also contains the high proportion of individuals who are incapable of speaking the official language of the province. For example, in Quebec, approximately 5% of Quebecers (or 1% of Canadians overall) reported that they can only speak English.[13]

Bilingualism by province/territory based on 2016 Canadian census data

| Province/Territory | Total population | Numbers of persons with knowledge of both official languages | Percentage of persons with knowledge of both official languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13,312,865 | 1,490,390 | 11.1% | |

| 8,164,361 | 3,586,410 | 43.9% | |

| 4,648,055 | 314,925 | 9.6% | |

| 4,067,175 | 264,720 | 6.5% | |

| 1,278,365 | 108,460 | 8.4% | |

| 1,098,352 | 51,360 | 4.7% | |

| 923,598 | 95,380 | 10.3% | |

| 747,101 | 249,950 | 33.4% | |

| 519,716 | 25,940 | 5.0% | |

| 142,907 | 17,840 | 12.5% | |

| 41,786 | 4,275 | 10.2% | |

| 35,874 | 4,900 | 13.7% | |

| 35,944 | 1,525 | 4.2% | |

| 35,151,728 | 6,216,065 | 17.7% |

Geographical distribution of all Canadians (pictured on left) and geographical distribution of bilingual Canadians (pictured on right)

Bilingualism rate in Canada's largest cities[edit]

According to Statistics Canada (2021),[25] rates of bilingualism in both official languages in Canada's ten largest cities are as follows:

| City | Bilingualism rate |

|---|---|

| Montreal | 59% |

| Quebec City | 43% |

| Ottawa | 36% |

| Winnipeg | 10% |

| Toronto | 9% |

| Vancouver | 9% |

| Calgary | 7% |

| Edmonton | 7% |

| Hamilton | 6% |

| Kitchener | 6% |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Joy, Richard, Languages in Conflict: The Canadian Experience, Carleton University Press, 1972, ISBN 0-7710-9761-1. (Originally self-published in 1967.)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Richard Joy, Languages in Conflict. Ottawa: Self-published, 1967, p. 21.

- ^ Richard Joy, Languages in Conflict. Ottawa: Self-published, 1967, p. 4.

- ^ Richard Joy, Languages in Conflict. Ottawa: Self-published, 1967, p. 20.

- ^ "Region of contact" is a term used by Joy in his later book, Canada's Official Languages: The Progress of Bilingualism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992. See p. 5, for example.

- ^ Richard Joy, Languages in Conflict. Ottawa: Self-published, 1967, p. 24.

- ^ Richard Joy, Languages in Conflict. Ottawa: Self-published, 1967, pp. 126-127.

- ^ Joy refers to seven counties on p. 20 of Languages in Conflict but does not specify their names. On p. 84 he refers to Gloucester, Kent, Madawaska and Restigouche counties, which implies that the three unnamed counties in this region must be Northumberland (which separates Kent County from Gloucester and Restigouche Counties), Victoria County (which lies to the south of Madawaska and Restigouche, and which contains the large bilingual town of Grand Falls / Grand-Sault), and Westmoreland County, which contains the bilingual city of Moncton.

- ^ In his initial description of this part of the bilingual belt on p. 20, Joy says only that it included "southern Quebec and the Ottawa Valley." However, in a later chapter he is much more precise. "Southern Quebec" means the "seven inner counties" (i.e. those closest to the Vermont border) of the Eastern Townships. These are Brome, Compton, Missisquoi, Richmond, Shefford, Sherbrooke and Stanstead counties. He also includes Huntingdon County, which lies to the west of the Richelieu River along the intersection of the Quebec, New York and Ontario borders, as being part of this grouping. (See p. 99.) "The Ottawa Valley" means Argenteuil, Gatineau, Hull, Papineau and Pontiac counties. (See p. 100.) He also specifies that the island of Montreal forms the most populous and important part of the bilingual belt.

- ^ Joy mentions the "eleven counties" on p. 20 of Languages in Conflict, but never lists them. References elsewhere in the book (in particular, a chart on p. 33) suggest that the counties are (from southeast to northwest): (1) Stormont County, (2) Glengarry County, (3) Prescott County, (4) Russell County, (5) Carleton County, (6) Renfrew County, (7) Nipissing District, (8) Timiskaming District, (9) Cochrane District, (10) Sudbury District, (11) Algoma District.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ a b "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ a b "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ a b "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E