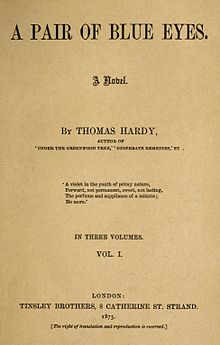

A Pair of Blue Eyes

First edition title page | |

| Author | Thomas Hardy |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Tinsley Brothers |

Publication date | 1873 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 3 volumes |

A Pair of Blue Eyes is a novel by Thomas Hardy, first serialised between September 1872 and July 1873, in Tinsley's Magazine, and published in book form in 1873. It was Hardy's third published novel, and the first not published anonymously. Hardy included it with his "romances and fantasies".

Plot[edit]

The book describes the love triangle of a young woman, Elfride Swancourt, and her two suitors from very different backgrounds. Stephen Smith is a socially inferior but ambitious young man who adores her and with whom she shares a country background. Henry Knight is the respectable, established, older man who represents London society. Although the two are friends, Knight is not aware of Smith's previous liaison with Elfride.

Elfride finds herself caught in a battle with her heart, her mind and the expectations of those around her – her parents and society. When Elfride's father finds that his guest and candidate for his daughter's hand, architect's assistant Stephen Smith, is the son of a mason, he immediately orders him to leave. Knight, who is a relative of Elfride's stepmother, is later on the point of seeking to marry Elfride, but ultimately rejects her when he learns she had been previously courted.

Elfride, out of desperation, marries a third man, Lord Luxellian. The conclusion finds both suitors travelling together to Elfride, both intent on claiming her hand, and neither knowing either that she already is married nor that they are accompanying her corpse and coffin as they travel.

The novel has various settings including gothic churches, coastal cliffs, hills, valleys, and beaches.

Characters[edit]

Elfride Swancourt, the heroine, is both extremely attractive and emotionally naive; a Victorian Miranda.[1]

Stephen Smith, her first suitor, also has this childish innocence, and she loves him because he is "so docile and gentle" (chapter 7).

Henry Knight, the second suitor, is more dominantly masculine, with the expectation of Elfride's spiritual and physical virginity.[2]

Background[edit]

This was the third of Hardy's novels to be published and the first to bear his name. It was first serialised in Tinsley's Magazine between September 1872 and July 1873.

The novel is notable for the strong parallels to Hardy and his first wife Emma Gifford. In fact, of Hardy's early novels, this is probably the most densely populated with autobiographical events.[3]

Reception[edit]

A review in the Examiner of Far from the Madding Crowd retrospectively referred to it as "not so exclusively pictoral [as Under the Greenwood Tree]; it was study of a more tragic kind, with more complex characters and a more stirring plot... Both Under the Greenwood Tree and A Pair of Blue Eyes are very remarkable novels, which no one could read without admiring the close and penetrating observation, and pictoral and narrative power of the writer."[4]

Late in his life, Hardy met composer Sir Edward Elgar and discussed the possibility of Elgar basing an opera on the novel. Hardy's death put an end to the project.[citation needed]

BBC Radio 4 recorded the book as a serial, with Jeremy Irons as Harry Knight.

Literary criticism[edit]

A Pair of Blue Eyes normally is categorised as one of Hardy's minor works, "a book with a few good points but a failure as a whole".[2][3] Like Desperate Remedies, it contains melodramatic scenes that appear disconnected from the characters and plot.[3]

A focus of critical interest of the novel is the scene in which Henry Knight reviews the entire history of the world as he hangs over the edge of a cliff (reputedly the origin of the term "cliffhanger"), and eventually is rescued by a rope of Elfride's underwear. Carl J. Weber sources the scene to a picnic Hardy and his wife had, in which he was sent to search for a lost earring, claiming this passage is the "first indication in the novels of Hardy's ability to sustain interest in a tense situation by sheer power of vivid description."[5] On the other hand, Millgate claims the scene forms part of the "irrelevant" description suited to the "rag-bag" of a novel.[5] For Jean Brooks, the scene is "macabre" and an illustration of "cosmic indifference", also highlighting the comic in the rescue.[5]

However, Gittings and Halperin claim it is more likely the idea for this scene comes from an essay by Leslie Stephen titled "Five minutes in the Alps". The "cliff without a name", as it is referred to, is probably based on Beeny Cliff.[5]

References[edit]

- ^ see article, which describes her as "openly compassionate and unaware of the evils of the world that surrounds her".

- ^ a b Steig, Michael (Spring 1970). "The Problem of Literary Value in Two Early Hardy Novels". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 12 (1): 55–62. JSTOR 40754081.

- ^ a b c Wittenburg, Judith Bryant (Winter 1983). "Early Hardy Novels and the Fictional Eye". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. 16 (2): 151–164. doi:10.2307/1345082. JSTOR 1345082.

- ^ Minto, W (5 December 1874). "Far from the Madding Crowd". Examiner.

- ^ a b c d Halperin, John (October 1980). "Leslie Stephen, Thomas Hardy, and 'A Pair of Blue Eyes'". The Modern Language Review. 75 (4): 738–745. doi:10.2307/3726582. JSTOR 3726582.

External links[edit]

- A Pair of Blue Eyes at Standard Ebooks

- A Pair of Blue Eyes at Project Gutenberg

A Pair of Blue Eyes public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Pair of Blue Eyes public domain audiobook at LibriVox