Sámi history

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

The Sámi people (also Saami) are a Native people of northern Europe inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses northern parts of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The traditional Sámi lifestyle, dominated by hunting, fishing and trading, was preserved until the Late Middle Ages, when the modern structures of the Nordic countries were established.

The Sámi have co-existed with their neighbors for centuries, but for the last two hundred years, especially during the second half of the 20th century, there have been many dramatic changes in Sámi culture, politics, economics and their relations with their neighboring societies. During the late 20th century, conflicts broke out over the use of natural resources, the reaction to which created a reawakening and defense of Sámi culture in recent years. Of the eleven different historically attested Sámi languages (traditionally known as "dialects"), only nine have survived to the present day but with most in danger of disappearing too.

It is possible that the Sámi people's existence was documented by such writers as Tacitus. They have on uncertain grounds, but for a very long time, been associated with the Fenni. However, the first Nordic sources date from the introductions of runes and include specifically the Account of the Viking Othere to King Alfred of England.

Prehistory[edit]

The area traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people is known in Northern Sámi as Sápmi, and typically includes the northern parts of Fennoscandia. Previously, the Sámi have probably inhabited areas further south in Fennoscandia.[1] A few Stone Age cultures in the area had been speculated, especially in the 18th and early 19th centuries, to be associated with the ancestors of the Sámi, though this has been dismissed by modern scholars and extensive DNA testing.

Stone Age[edit]

The commonly held view today is that the earliest settlement of the Norwegian coast belongs to one cultural continuum comprising the Fosna culture in southern and central Norway and what used to be called the Komsa culture in the north. The cultural complex derived from the final Palaeolithic Ahrensburg culture of northwestern Europe, spreading first to southern Norway and then very rapidly following the Norwegian coastline when receding glaciation at the end of the last ice age opened up new areas for settlement. The rapidity of this expansion is underlined by the fact that some of the earliest radiocarbon dates are actually from the north.

The term "Fosna" is an umbrella term for the oldest settlements along the Norwegian coast, from Hordaland to Nordland. The distinction made with the "Komsa" type of stone-tool culture north of the Arctic Circle was rendered obsolete in the 1970s. "Komsa" itself originally referred to the whole North Norwegian Mesolithic, but the term has since been abandoned by Norwegian archaeologists who now divide the northern Mesolithic into three parts, referred to simply as phases 1, 2, and 3.[2][3] The oldest Fosna settlements in Eastern Norway are found at Høgnipen in Østfold. A Neolithic individual from Steigen and other Scandinavian individuals revealed admixture from Eastern Hunter-Gatherers and Western Hunter-Gatherers, suggesting migrations from the core regions of both populations into Northern Norway and Scandinavia as a whole.[4] This mixed ancestry prevailed all the way to the Late Neolithic as evidenced by an individual from Tromsø.[5]

Origin[edit]

The genetic origin of the Sámi is still unknown, though recent genetic research may be providing some clues.

Lamnidis et al. 2018 discovered the earliest recorded introgression of Nganasan related Siberian ancestry and Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup N1c into northeastern Europe. Saami people's Siberian ancestry varies between 20%-25%, while the bronze age individuals from Bolshoy Oleny Island by the Kola peninsula had around 40% of similar ancestry, accompanied with roughly 50% Mesolithic Eastern Hunter-Gatherer ancestry. This admixture event was estimated to have occurred around 2000 BCE by ALDER dating.[6] Sarkissian et al. 2013 reporting on a larger array of individuals from Bolshoy Oleny Island showed the prevalence of the mtDNA haplogroup U5a1 and other subclades of U and C typical to the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of the time, but also atypical D, T and Z.[7]

Archeological evidence suggests that people along the southern shores of Lake Onega and around Lake Ladoga reached the River Utsjoki in Northern Finnish Lapland before 8100 BC.[8] However, it is not likely that Sami languages are so old. According to the comparative linguist Ante Aikio, the Sami proto-language developed in South Finland or in Karelia around 2000–2500 years ago, spreading then to northern Fennoscandia.[9]

The genetic lineage of the Sami is unique, and may reflect an early history of geographic isolation, genetic drift, and genetic bottle-necking. The uniqueness of the Sami gene pool has made it one of the most extensively studied genetic populations in the world. The most frequent Sami MtDNA (female) haplotype is U5b1b1 comprising nearly half of all haplotypes, with type V in around the same quantities, with some minor D, H and Z.[10]

Before the 15th century[edit]

Historically, the Sámi inhabited all of Finland and Eastern Karelia for a long time, though the Eastern Sámi became assimilated into the Finnish and Karelian populations after settlers from Häme, Savo, and Karelia migrated into the region. Place names, such as Nuuksio on the south coast of Finland, have been claimed to prove former Sámi settlement.[11] However, the Sámi people increasingly mixed with Finnish and Scandinavian settlers, losing their culture and language.[12] Placename evidence suggesting a former Sámi presence in northwestern Russia (Arkhangelsk Region and the Vologda Region) has also been identified.[13] However, this may alternatively indicate a former population speaking a language related to but distinct from Sami proper.[14]

How far south the area of Sámi population in Norway extended in the past is an uncertain topic, and is currently debated among historians and archeologists. The Norwegian historian Yngvar Nielsen was commissioned by the Norwegian government in 1889 to determine this question in order to settle the contemporary question of Sámi land rights. He concluded that the Sámi had lived no further south than Lierne in Nord-Trøndelag county until around 1500, when they had started moving south, reaching the area around Lake Femunden in the 18th century.[15] This hypothesis is still accepted among many historians, but has been the subject of scholarly debate in the 21st century. In favour of Nielsen's view, it is pointed out that no Sámi settlement to the south of Lierne in medieval times has left any traces in written sources. This argument is countered by pointing out that the Sámi culture was nomadic and non-literary, and as such would not be expected to leave written sources.[16] In recent years, the number of archaeological finds that are interpreted as indicating a Sámi presence in Southern Norway in the Middle Ages has increased. These include foundations in Lesja, in Vang in Valdres and in Hol and Ål in Hallingdal.[16] Proponents of the Sámi interpretations of these finds assume a mixed population of Norse and Sámi people in the mountainous areas of Southern Norway in the Middle Ages.[17]

Up to around 1500 the Sámi were mainly fishermen and trappers, usually in a combination, leading a nomadic lifestyle decided by the migrations of the reindeer. Around 1500, due to excessive hunting, again provoked by the Sámi needing to pay taxes to Norway, Sweden and Russia, the number of reindeer started to decrease. Most Sámi then settled along the fjords, on the coast and along the inland waterways to pursue a combination of cattle raising, trapping and fishing. A small minority of the Sámi then started to tame the reindeer, becoming the well-known reindeer nomads, who, although often portrayed by outsiders as following the archetypical Sami lifestyle, only represent around 10% of the Sami people.

It is believed that since the Viking Age, Sámi culture has been driven further and further north, perhaps mostly by assimilation since no findings yet support battles. However, there is some folklore called stalo or 'tales', about non-trading relations with a cruel warrior people, interpreted by Læstadius to be histories of Vikings interactions. Besides these considerations, there were also foreign trading relations. Animal hides and furs were the most common commodities and exchanged with salt, metal blades and different kinds of coins. (The latter were used as ornaments).

Along the Northern Norwegian coast, the Sámi culture came under pressure during the Iron Age by expanding Norse settlements and taxation from powerful Norse chieftains. The nature of the Norse-Sami relationship along the North-Norwegian coast in the Iron Age is still hotly debated, but possibly the Sámi were quite happy to ally themselves with the Norse chieftains, as they could provide protection against Finno-Ugric enemies from the area around the White Sea.

However, in the early Middle Ages, this is partly reversed, as the power of the chieftains is broken by the centralized Norwegian state. Another wave of Norse settlement along the coast of Finnmark province is triggered by the fish trade in the 14th century. However, these highly specialized fishing communities made little impact on the Sámi lifestyle, and in the late Middle Ages, the two communities could exist alongside each other with little contact except occasional trading.

Sámi art[edit]

Traditionally, Sámi art has been distinguished by its combination of functional appropriateness and vibrant, decorative beauty. Both qualities grew out of a deep respect for nature, embodied in the Sámi's animism. Sámi religion found its most complete expression in Shamanism, evident in their worship of the seite, an unusually shaped rock or tree stump that was assumed to be the home of a deity. Pictorial and sculptural art in the Western sense is a 20th-century innovation in Sámi culture used to preserve and develop key aspects of a pantheistic culture, dependent on the rhythms of the seasons.[18]

An economic shift[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

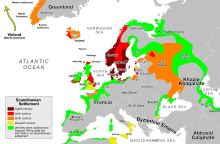

From the 15th century on, the Sámi came under increased pressure. The surrounding states, Denmark-Norway, Sweden and Russia showed increased interest in the Sámi areas. Sweden, at the time blocked from the North Sea by Dano-Norwegian territory, was interested in a port at the Atlantic coast, and Russian expansion also reached the coasts of the Barents Sea. All claimed the right to tax the Sámi people, and Finnish-speaking tax collectors from the northern coast of the Gulf of Bothnia reached the northern coasts, their Russian colleagues collected taxes as far west as the Harstad area of Norway and the Norwegian tax collectors collected riches from the inland of the Kola peninsula.

Hence the hunting intensified, and the number of wild reindeer declined. The Sámi were forced to do something else. Reindeer husbandry started in a limited way. These tamed reindeer were trained to divert wild reindeer over a cliff or into hunting ditches. Reindeer husbandry intensified.

The majority of Sámi settled along the inland rivers, fjords or coast. They started augmenting their diet and income by fishing, either sea or freshwater, hunting other game and keeping cows, sheep and goats.

Reindeer and other animals play a central part in Sami culture, though today reindeer husbandry is of dwindling economic relevance for the Sámi people. There is currently (2004) no clear indication when reindeer-raising started, perhaps about 500 AD, but tax tributes were raised in the 16th century. Since the 16th century, Samis have always paid taxes in monetary currency, and some historians have proposed that large scale husbandry is not older than from this period.

Lapponia (1673), written by the rhetorician Johannes Schefferus, is the oldest source of detailed information on Sámi culture. It was written due to "ill-natured" foreign propaganda (in particular from Germany) claiming that Sweden had won victories on the battlefield by means of Sámi magic. In attempts to correct the picture of Sámi culture amongst the Europeans, Magnus de la Gardie started an early 'ethnological' research project to document Sámi groups, conducted by Schefferus. The book was published in late 1673 and quickly translated to French, German, English, and other languages (though not to Swedish until 1956). However, an adapted and abridged version was quickly published in the Netherlands and Germany, where chapters on their difficult living conditions, topography, and the environment had been replaced by made-up stories of magic, sorcery, drums and heathenry. But there was also criticism against the ethnography, claiming Sámi to be more warlike in character, rather than the image Schefferus presented.

Swedish advances into Sápmi[edit]

Since the 15th century, the Sámi people have traditionally been subjects of Sweden, Norway, Russia and for some time Denmark. In the 16th century Gustav I of Sweden officially claimed that all Sámi should be under Swedish realm. However, the area was shared between the countries (i.e. only Sweden and Norway—at that time the Baltic-Finnic tribes of the region that is now Finland were also subjects of Sweden) and the border was set up to be the water flux line in Fennoscandia. After this "unification", the society, a structure with a few ruling and wealthy citizens called birkarls, ceased to exist, especially with the new king Charles IX who swore by his crown to be the "... Lappers j Nordlanden, the Caijaners" king 1607.[19] During the enforced Christianization of the Sámi people, yoiking, drumming and sacrifices were now abandoned and seen as (juridical terms) "magic" or "sorcery", something that was probably aimed at removing opposition against the crown. The hard custody of Sámi peoples resulted in a great loss of Sámi culture.

In the 1630s Swedish authorities imposed a corveé system on Sámi communities near the Nasa silver mine.[20][21] Mining at the Nasa silver mine proved unprofitable and ended in 1659 it nevertheless caused many Sámi to move to Torne lappmark in the 1640s and 1650s to avoid forced labour.[21] There are reports of Sámi who served in the mining activities becoming extremely impoverished, becoming beggars in consequence.[21]

The boundary agreement between Sweden and Norway (Stromstad Treaty of 1751) had an annex, frequently called Lapp Codicil of 1751, Lappkodicillen or "Sami Magna Carta". It has the same meaning for Sámi even today (or at least till 2005), but is only a convention between Sweden and Norway and does not include Finland and Russia. It regulates how the land is shared by Sámi peoples between the border of Sweden and Norway.

After the 17th century, many Sámi families lost the right to use Swedish land since they were poor and could not pay tribute for it like other subjects. The state also took the Sámi area in tighter control with specific Lappmark Regulations, enforcing non-Sámi settlements on the area. This fostered opposition among Sámi groups that wanted hunting, fishing, and pastoralistic areas back. Instead other groups often took over to put more use to the land. It was also at this time the county of Lappland was established in Sweden.

Russian interest[edit]

In the 16th century, as part of a general expansion period for the Russian empire, missionaries were sent to the far reaches of the empire, and several Russian Orthodox chapels were built on the Kola Peninsula. The westernmost advance was St. George's chapel in Neiden/Njavdam near Kirkenes in the Norwegian/Russian borderlands.

Dano-Norwegian policies in the North[edit]

On the Norwegian side, the Sámi were converted to the Lutheran faith around 1720. Thomas von Westen was the leading man of the missionary effort, and his methods included the burning of shamanic drums. However, economically the Sámi were not that badly off, compared to the Norwegian population. They were free to trade with whom they wanted, and entertained trade links with Norwegians and Russians alike. However, the crumbling economy of the Norwegian communities along the outer coast led to increased pressure on the land and conflicts between the two communities.

19th century: Increased pressure[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

The 19th century led to increased interest in the far north.

New borders in an old land[edit]

In 1809, Finland was seized by Russia, creating a new border right through the Sámi area. In 1826, the Norwegian/Russian border treaty finally drew the border between Norway and Finland-Russia, where large tracts of land had previously been more or less governing themselves under very light joint control from Russia, Sweden and Denmark-Norway. This meant that reindeer herders who until now had stayed in Finland in Winter and on the Norwegian coast in Summer, could no longer cross the borders. The Norwegian/Swedish border, however, could still be crossed by reindeer herders until 1940.

The Sámi crossed the borders freely until 1826, when the Norwegian/Finnish/Russian border was closed. Sámi were still free to cross the border between Sweden and Norway according to inherited rights laid down in the Lapp Codicil of 1751 until 1940, when the border was closed due to Germany's occupation of Norway. After World War II, they were not allowed to return. Their summer pasturages are today used by Sámi originating in Kautokeino.

For long periods of time, the Sámi lifestyle reigned supreme in the north because of its unique adaptation to the Arctic environment, enabling Sámi culture to resist cultural influences from the South. Indeed, throughout the 18th century, as Norwegians of Northern Norway suffered from low fish prices and consequent depopulation, the Sámi cultural element was strengthened, since the Sámi were independent of supplies from Southern Norway.

Economic marginalization[edit]

In all the Nordic countries, the 19th century was a period of economic growth. In Norway, cities were founded and fish exports increased. The Sámi way of life became increasingly outdated, and the Sámi were marginalized and left out of the general expansion.

Christianization and the Laestadius Movement[edit]

In the 1840s, the Swedish Sámi minister, Lars Levi Laestadius, preached a particularly strict version of the Lutheran teachings. This led to a religious awakening among the Sámi across every border, often with much animosity towards the authorities and the established church. In 1852, this led to riots in the municipality of Kautokeino, where the minister was badly beaten and the local tradesman slain by fanatic "crusaders". The leaders of the riots were later executed or condemned to long imprisonment. After this initial violent outbreak, the Laestadius movement continued to gain ground in Sweden, Norway and Finland. However, the leaders now insisted on a more cooperative attitude with the authorities.

Cultural pressure[edit]

In Norway, the use of Sámi in teaching and preaching had initially been encouraged. However, with the rise in nationalism in Norway from the 1860s onward, the Norwegian authorities changed their policies in a more nationalistic direction. From around 1900 this was intensified, and no Sámi could be used in public school or in the official church.

The early 20th century through World War II[edit]

In the 20th century, Norwegian authorities put the Sámi culture under pressure in order to make the Norwegian language and culture universal. A strong economical development of the north also took place, giving Norwegian culture and language status. On the Swedish and Finnish side, the authorities were much less militant in their efforts; however, strong economic development in the north led to a weakening of status and economy for the Sámi.

The strongest pressure took place from around 1900 to 1940, when Norway invested considerable money and effort to wipe out Sámi culture. Notably, anyone who wanted to buy or lease state lands for agriculture in Finnmark, had to prove knowledge of the Norwegian language. This also ultimately caused the dislocation in the 1920s, that increased the gap between local Sámi groups, something still present today, and sometimes bears the character of an internal Sámi ethnic conflict.

Just as every portion of the European continent, the circumpolar lands of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Soviet Union were not spared the wrath of World War II. For the Sámi, who had no concept of national sovereignty, the concept of nations fighting over land was alien. Nevertheless, the Sámi would become entrapped in the conflict from all sides. Another factor was the heavy war destruction in northern Finland and northern Norway in 1944–45, destroying all existing houses and visible traces of Sámi culture. After World War II, the pressure was relaxed somewhat.

Prewar hardliners in Norway[edit]

The 20th century started with increased pressure on the Norwegian side of the border. In the name of progress, Norwegian language and culture was promoted, and Sámi language and culture were dismissed as backward, uncultured, downright ridiculous and even the product of an inferior race. Land that previously belonged to no one, and was used according to age-old principles, was considered state property. Settlers had to prove they could speak Norwegian well before they could claim new land for agriculture.

Sweden[edit]

In Sweden, the policies were at first markedly less militant. Teachers followed Sámi reindeer herders to provide education for the children, but Sámi areas were increasingly exploited by the then new mines in Kiruna and Gällivare and the construction of the Luleå-Narvik railway.

Later, with the founding of the Swedish Race Biology Institute, Sámi graves were plundered to provide research material.[22][23]

Russia[edit]

In Russia, the age-old ways of life of the Sámi were brutally interrupted by the collectivization of the reindeer husbandry and agriculture in general. Most Sámi were organized in a single kolkhoz, located in the central part of the Peninsula, at Lovozero (Sámi: Lojavri). The Soviet state made an enormous effort to develop this strategically important region, and the Sámi people witnessed their land being overrun by ethnic Russians and other Soviet nationalities, including Nenets and other Arctic peoples.

Winter War (1939–40)[edit]

The first fighting Saami became entangled in was between Finland and the Soviet Union during the Winter War in 1939 when the Soviet Union invaded Finland after the Soviets were denied the ability to construct military bases there. The Red Army, believing that they could easily march across Finland to the Gulf of Bothnia, made the mistake of invading Finland during an unusually cold winter and suffered 27,000 casualties compared to the Finnish mere 2,700. However, as the weather warmed in March 1940, the Finnish line was breached and facing the far larger Soviet forces, was forced to sue for peace on March 12.[24]

German invasion and occupation of Norway[edit]

On April 9, 1940, Hitler began Operation Weserübung and invaded Norway. With assistance from former Norwegian Defense Minister and Nazi sympathizer Vidkun Quisling, the Germans were quickly able to gain a foothold. The Nazis viewed ethnic “Nordic Norwegians”, who are Germanic and oftentimes blonde-haired and blue-eyed, as Aryans just like Germans. Quisling shared their view and proposed the complete eradication of the Sámi people, who he viewed as ethnically inferior. Despite the urging of Winston Churchill, British support for the Norwegians was appallingly slow, an action that was responsible for making him prime minister. As a result, the Nazis easily captured the northern port of Narvik. Despite a blockade by the British Royal Navy, the German Wehrmacht were able to hide in the mountains by forcing local Sámi to serve as guides.[24]

On April 20, 1940, King Haakon and the Norwegian government fled to London along with most of the Allied troops stationed there and formed a government in exile. However, Norwegians continued fighting the Nazis through underground resistance. These resistance fighters included many Sámi who had formerly served as part of the Norwegian Ski Brigade and were instrumental in destroying a secret German nuclear base in Telemark in 1944. However, many other Norwegian Sámi were forced into labor by the SS to mine iron ore and build a railway from Narvik to Finland through Finnmark. Forced sterilizations and deportations were also not uncommon.[24]

Continuation War[edit]

At the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler offered Finland assistance in recapturing the lost territory to the Soviets (some of which, e.g. Pachenga/Petsamo Finland conquered for the first time in the midst of the Russian Revolution). However, Finland never formally joined the Axis powers, but did closely cooperate with the Germans – including deporting at least some Jews to German camps.[25] The Finns with assistance from the SS Nord invaded Kola on June 1, 1941. Most Finnish Saami served as part of the “Long Distance Patrol” because of their abilities on skis and familiarity with the terrain.[24]

Unfortunately, Finnish Saami, being supplied by forced labor of Norwegian Saami, were forced to fight Russian Saami during the Continuation War. With Finnish assistance, many Saami villages in the Soviet territory were evacuated for the remainder of the war. However, other Saami were not so lucky and along with many other Soviet soldiers and civilians were placed in prison and even concentration camps. This angered the Finnish government, who also refused to assist the Wehrmacht in seizing Leningrad. Eventually the tide turned in favor of the Red Army and Soviet troops marched back into Finland and on June 9, 1944, the Red Army got within striking distance of Helsinki. The Finns sued for peace and lost much territory, including a large part of Saami.[24]

Lapland War (1944–45)[edit]

As a result of Finland's peace deal with the Soviets, German troops were required to leave the country. The withdrawal of the German Wehrmacht from Northern Finland and far north of Norway meant that all houses, roads and infrastructure were destroyed. This meant forced evacuation, destruction, an economic setback and the loss of all visible history. The Germans committed many atrocities against the Norwegians and Norwegian Saámi during the Lapland War, including raping hundreds of women, many of whom committed suicide because of the trauma. The Finnmark province, the north-eastern municipalities of Troms province and all of the northern areas of Finland were but smoking ruins. Eventually Soviet troops fully invaded Sampi with the assistance of the Norwegian Army in Exile and liberated Finnmark. On April 26, 1945, Finnmark was liberated.

Renewed interest[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

News in Sámi on national radio in Norway started in 1946. At about the same time, experiments were being done with bilingual teachings of the alphabet in the first and second grade, to ease the learning process. However, the presence of a Sámi minority in Norway was largely ignored. Education, communication, industrialization, all contributed to integrating Sámi communities into Norwegian society at the point of losing identity.

The conflicts between Sámi and the Nordic governments continued into the mid 20th century. The proposed construction of the hydro power dam in the 1960s and 1970s contained controversial propositions such as putting a village (Máze) and a cemetery under water.

Only a minor part is today working with reindeer husbandry. There are also minor groups working as fishermen, producing Sámi arts and serving tourism. Besides having a voting length in the Sámi parliaments (with differing levels of authority and autonomy in various countries) or influence in any Sámi language, the rest are ordinary citizens, adhering to the Scandinavian culture. In Sweden, major parts of Norrland (and not only Sámi villages) are also experiencing major emigration to larger towns.

With the creation of the Republic of Finland in the first half of the 20th century, the Sámi inhabiting this area were no longer under the rule of the Russian Empire, but instead citizens of the newly created state of Finland. The Sámi Parliament of Finland was created in 1973. One recent issue concerning Sámi rights in Finland is the foresting of traditional Sámi land by state-owned Finnish companies.

Since 1992, the Sámi have had their own national day; the February 6.

In 1898 and 1907/08 some Sámi emigrated to Alaska and Newfoundland, respectively, due to requests from the American government. Their mission was to teach reindeer herding to Native Americans.

Assimilated Sámi[edit]

Kainuu Sámi was spoken in Kainuu, but became extinct in the 1700s. Kainuu Sámi belonged to the Eastern Sámi language group. It died out when the Kainuu Sámi assimilated and was replaced by Finnish.

The original inhabitants of Kainuu were Sámi hunter-fisherers. In the 17th century, the Governor General of Finland Per Brahe fostered the population growth of Kainuu by giving a ten-year tax exemption to settlers. It was necessary to populate Kainuu with Finnish farmers because the area was threatened from the east by the Russians.

There are only 14,600 Sámi living in Sweden today.[26]

Already the ancient Romans knew about the Phinnoi, the people that hunted with arrowheads made from bone. The Scandinavian historical sources from the Middle Ages praise the archery skills of the Sámi as well as their strong bows which a Norwegian “could not string”. The North Sámi called this bow juoksa. A boy turned into a man when he was able to string the bow. At that point, he also had to start paying taxes.

— "Juoksa – The Sámi Bow", Siida, 2010[27]

Lapland War 1944–1945 in World War II[edit]

Waffen-SS (6. SS-Gebirgs-Division Nord) were fighting in the Lapland War. There were encounters between the Sámi people and the Germans. The assimilated Sámi would have been fighting in the Finnish army.

-

December 1940

-

1942

-

23 September 1943

-

23 September 1943

-

23 September 1943

-

23 September 1943

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Samenes Historie fram til 1750. Lars Ivar Hansen and Bjornar Olsen. Cappelen Akademiske Forlag. 2004

- ^ "Norway" Britannica online

- ^ Olsen, B. 1994. Bosetning og samfunn i Finnmarks forhistorie. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget

- ^ Günther, Torsten; Malmström, Helena; Svensson, Emma M.; Omrak, Ayça; Sánchez-Quinto, Federico; Kılınç, Gülşah M.; Krzewińska, Maja; Eriksson, Gunilla; Fraser, Magdalena; Edlund, Hanna; Munters, Arielle R. (2018-01-09). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

- ^ Margaryan, Ashot; Lawson, Daniel J.; Sikora, Martin; Racimo, Fernando; Rasmussen, Simon; Moltke, Ida; Cassidy, Lara M.; Jørsboe, Emil; Ingason, Andrés; Pedersen, Mikkel W.; Korneliussen, Thorfinn (September 2020). "Population genomics of the Viking world". Nature. 585 (7825): 390–396. Bibcode:2020Natur.585..390M. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2688-8. hdl:10852/83989. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32939067. S2CID 221769227.

- ^ Lamnidis, Thiseas C.; Majander, Kerttu; Jeong, Choongwon; Salmela, Elina; Wessman, Anna; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Khartanovich, Valery; Balanovsky, Oleg; Ongyerth, Matthias; Weihmann, Antje; Sajantila, Antti (2018-11-27). "Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.5018L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6258758. PMID 30479341.

- ^ Sarkissian, Clio Der; Balanovsky, Oleg; Brandt, Guido; Khartanovich, Valery; Buzhilova, Alexandra; Koshel, Sergey; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; Gronenborn, Detlef; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Kolpakov, Eugen; Shumkin, Vladimir (2013-02-14). "Ancient DNA Reveals Prehistoric Gene-Flow from Siberia in the Complex Human Population History of North East Europe". PLOS Genetics. 9 (2): e1003296. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003296. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 3573127. PMID 23459685.

- ^ Uncovering the secrets of the Sámi, a February 2006 Helsingin Sanomat article

- ^ Aikio, Ante (2004). "An essay on substrate studies and the origin of Saami". In Hyvärinen, Irma; Kallio, Petri; Korhonen, Jarmo (eds.). Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen: Festschrift für Jorma Koivulehto zum 70. Geburtstag. Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki. Vol. 63. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique. pp. 5–34.

- ^ Tambets, Kristiina; Rootsi, Siiri; Kivisild, Toomas; Help, Hela; Serk, Piia; Loogväli, Eva-Liis; Tolk, Helle-Viivi; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Pliss, Liana; Balanovsky, Oleg (April 2004). "The Western and Eastern Roots of the Saami—the Story of Genetic "Outliers" Told by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (4): 661–682. doi:10.1086/383203. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181943. PMID 15024688.

- ^ Etymologies of the names of the districts of Espoo (in Finnish).[dead link]

- ^ Aikio, Ante (2012). "An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory". Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 266. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society: 63–117. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Matveev, A. K. (2007). "Saami Substrate Toponymy in Northern Russia" (PDF). Borrowing of Place Names in the Uralian Languages. Onomastica Uralica. Vol. 4. pp. 129–139. ISBN 978-963-473-100-9. ISSN 1586-3719.

- ^ Helimski, Eugene (2006). "The "Northwestern" Group of Finno-Ugric Languages and its Heritage in the Place Names and Substratum Vocabulary" (PDF). In Nuorluoto, Juhani (ed.). The Slavicization of the Russian North: Mechanisms and Chronology. Slavica Helsingiensia. Vol. 27. pp. 109–127 of the Russian North. ISBN 978-952-10-2928-8. ISSN 0780-3281.

- ^ Yngvar Nielsen (1891). "Lappernes fremrykning mod syd i Trondhjems stift og Hedemarkens amt" [The incursion of Lapps southwards in the see of Trondhjem and county of Hedemarken]. Det Norske Geografiske Selskabs årbog (in Norwegian). 1 (1889–1890). Kristiania: 18–52.

- ^ a b Hege Skalleberg Gjerde (2009). "Samiske tufter i Hallingdal?" [Sami foundations in Hallingdal?]. Viking (in Norwegian). 72 (2009). Oslo: Norwegian Archaeological Society: 197–210.

- ^ : 208

- ^ Grove Dictionary of Art, ISBN 1-884446-00-0

- ^ Titles of European hereditary rulers - Sweden Konung Christoffers Landslag. Edictum Regis Caroli IX eius iussu edito textui praescriptum

- ^ Hansson 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Hansson 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Museum of Dalarna "The dark legacy" exhibition in Sweden. 2007.

- ^ Savage, James (31 May 2010). "University in quest to return Sami bones". The Local: Sweden's News in English.

- ^ a b c d e "The Sami and World War II". www.laits.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ Silvennoinen, Oula (2013), Muir, Simo; Worthen, Hana (eds.), "Beyond "Those Eight": Deportations of Jews from Finland 1941–1942", Finland’s Holocaust: Silences of History, The Holocaust and its Contexts, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 194–217, doi:10.1057/9781137302656_9, ISBN 978-1-137-30265-6

- ^ Languages of Sweden, Ethnologue.

- ^ "Juoksa – The Sámi Bow – Siida". Siida. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

Books[edit]

- Hansson, Staffan (2015). Malmens Land: Gruvnäringen i Norrbotten under 400 år (in Swedish). Tornedalica. ISBN 978-91-972358-9-1.

External links[edit]

- Historiska nyheter No. 62

- A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. 1

- Sámi Emigration to America

- Sámi Genetic Information

- The Saami Culture, University of Texas

- Coexistence of Saami and Norse culture reflected in and interpreted by Old Norse myths, Mundal

- Ohthere's Voyage (890 AD) original text with English translation

- The Origin and Deeds of the Goths by Jordanes (551 AD)

- Germania by Tacitus (98 AD)

- The Western and Eastern Roots of the Saami—the Story of Genetic "Outliers" Told by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomes, Tambets 2004

- Saami Mitochondrial DNA Reveals Deep Maternal Lineage Clusters, Delghandi 1998

- Saami and Berbers—An Unexpected Mitochondrial DNA Link, Achilli 2005

- Documentary: The Only Image of My Father. The adult daughter of a Sami man, whom she has never met, and who is depicted on a postage stamp, visits present day surviving Sami people looking for her father. [1]