Shadow of the Vampire

| Shadow of the Vampire | |

|---|---|

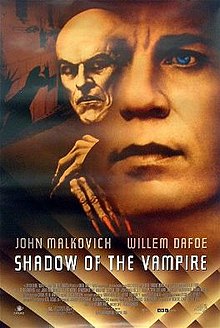

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | E. Elias Merhige |

| Written by | Steven Katz |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Lou Bogue |

| Edited by | Chris Wyatt |

| Music by | Dan Jones |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $8 million[2] |

| Box office | $11.2 million[3] |

Shadow of the Vampire is a 2000 independent period vampire mystery film directed by E. Elias Merhige and written by Steven Katz. The film stars John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe. It is a fictionalized account of the making of the classic vampire film Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, directed by F. W. Murnau, during which the film crew begin to have disturbing suspicions about their lead actor.

The film borrows the techniques of silent films, including the use of intertitles to explain elided action, and iris lenses. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Makeup, losing to How the Grinch Stole Christmas. For his performance, Dafoe was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[4]

Plot[edit]

In 1921, German director F. W. Murnau is shooting Nosferatu, an unauthorized version of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula. Murnau keeps his team in the dark about their schedule and the actor playing the vampire Count Orlok. It is left to the film's other main actor, Gustav von Wangenheim, to explain that the lead is an obscure German theater performer named Max Schreck, who is a character actor. To involve himself fully in his role, Schreck will only appear amongst the cast and crew in makeup, will only be filmed at night, and will never break character.

After filming scenes in a studio with leading actress Greta Schröder, Murnau takes his cast and crew to a remote inn in Czechoslovakia to film on location. The landlady becomes distressed at Murnau removing crucifixes around the inn, and the cameraman, Wolfgang Muller, falls into a strange, hypnotic state. Gustav discovers a bottle of blood amongst the team's food supplies, and someone delivers a caged ferret in the night to a not yet fully revealed Schreck.

One night, Murnau rushes his team up to a nearby old Slovak castle for the first scene with the vampire. Schreck appears for the first time, and his appearance and behavior impress and disturb them. The film's producer, Albin Grau, is confused when Murnau tells him that he originally found Schreck in the castle. Soon after the completion of the scene, Wolfgang is found collapsed in the tunnel into which Schreck had receded.

While filming a dinner scene between Gustav and Schreck, Gustav accidentally cuts his finger. Schreck reacts wildly and tries drinking from Gustav's wound. The lights fail and when they return, Schreck is at Wolfgang's neck. Albin orders filming ended for the night, and the crew rushes from the castle, leaving Schreck behind. Alone, Schreck examines the camera equipment, fascinated by footage of a sunrise. With Wolfgang near death, Murnau is forced to bring in another cinematographer, Fritz Arno Wagner, after chastising Schreck in private for attacking his crew members. Murnau threatens Schreck with harm if he does not control himself in Murnau's absence—a threat that Schreck challenges due to his immortality.

While Murnau returns to Berlin to calm financiers of the film, Schreck approaches Albin and the screenwriter, Henrik Galeen, who believe he is still in character. Schreck points out Dracula's loneliness and the sadness of him trying to remember how to do otherwise mundane chores that he has not needed to perform for centuries. When they ask how he became a vampire, Schreck says it was a woman. Schreck snatches a bat and viciously sucks its blood. Grau and Galeen, thanks to their drunkenness on schnapps, are impressed by what they assume is talented acting. Later that night, Schreck attacks and kills a crew member on the film's set.

The production moves to the island of Heligoland to film the final scenes. Murnau, in a laudanum-induced stupor, admits to Albin and Fritz that Schreck is an actual vampire, and in return for his cooperation, Murnau has promised him Greta. The two realize they are trapped on the island, leaving no choice but to complete the film that night.

On set, Greta becomes hysterical after noticing Schreck casts no reflection. Murnau, Albin and Fritz drug her with Murnau's laudanum, and film as Schreck feeds on Greta, with the laudanum in her blood putting Schreck to sleep. At dawn, the three attempt to open a door and let in sunlight to destroy Schreck, but discover that the vampire had previously cut the chain to the mechanism, trapping them in the process. Fritz and Albin attack Schreck, only to be killed. Murnau resumes filming, and, crazed, completely ignores the deaths of his colleagues and the malicious glare Schreck is giving him. Instead, he instructs Schreck to return to his mark for another take. Schreck returns to feed on Greta as Murnau films. Galeen and the crew arrive and lift the door, destroying Schreck with the sunlight. Having become completely obsessed with the film, Murnau asks for an end slate to his rattled crew. After they oblige, he stops the camera and calmly states, "I think we have it."

Cast[edit]

- John Malkovich as Frederich Wilhelm Murnau, the director of Nosferatu

- Willem Dafoe as Max Schreck, who plays Count Orlok

- Cary Elwes as Fritz Arno Wagner, the cinematographer

- John Aden Gillet as Henrik Galeen, the screenwriter

- Eddie Izzard as Gustav von Wangenheim, who plays Thomas Hutter/Jonathan Harker

- Udo Kier as Albin Grau, occultist; the producer, art director, and costume designer

- Catherine McCormack as Greta Schröder, who plays Ellen Hutter/Mina Harker

- Ronan Vibert as Wolfgang Muller

- Nicholas Elliott as Paul

- Sophie Langevin as Elke

- Myriam Muller as Maria

Character details[edit]

The film depicts several of the major characters as being killed by the vampire; however, historically these individuals continued to live long lives after the film's production. Fritz Wagner and Albin Grau, who are shown having their necks snapped by Max Schreck, lived to the 1950s and 1970s respectively. Greta Schröder, who also did not actually die, continued to have a film career until the 1950s and died in 1980. She is also depicted as being a famous actress, but in fact, she was little known, and by the 1930s her roles had diminished to only occasional appearances. Of all the characters, Murnau died the soonest after the production of Nosferatu, killed in a car crash in California in 1931. The film's depiction of Murnau as ruthless and dictatorial is also inaccurate. He was known as a director with rare sensitivity.[5]

Production[edit]

The film's working title was Burned to Light, but Merhige decided to change the name of the film when Dafoe asked, "Who's Ed?"; the actor thought the title was Burn Ed to Light.[6]

The film was produced by Nicolas Cage's Saturn Films. Cage originally intended to play Schreck, but later cast Dafoe when he expressed interest in the role. Cage stated he always wanted Malkovich as Murnau. Members of the online game the Hollywood Stock Exchange were able to donate a small sum towards the film's production in exchange for listing their names on the DVD release of the film as "virtual producers".[7]

Producer Cage has previously acted with Malkovich in Con Air (1997) and Dafoe in Wild at Heart (1990) respectively.[8][9]

To create the aesthetic of old film, cinematographer Lou Bogue shot much of the film with Kodak Vision 800T film stock - a high speed specialty stock with very coarse grain - in Super 35mm format, which further enhanced the effect when cropped and enlarged to anamorphic.[10]

Release[edit]

Shadow of the Vampire had its world premiere at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival.[11] It was given a limited release in the United States on December 29, 2000.[12][7]

Home media[edit]

Shadow of the Vampire was released on DVD in widescreen format on March 29, 2001.[13] On January 5, 2010, In2Film released the film on Region 2 DVD.[14]

Reception[edit]

Critical reaction has been mostly positive with Dafoe's performance as Schreck/Orlok receiving particular praise.[15][16] The film holds an 81% approval rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 140 reviews, with an average rating of 6.9/10. The site's critical consensus states: "Shadow of the Vampire is frightening, compelling, and funny, and features an excellent performance by Willem Dafoe."[17] On Metacritic, the film has a 71 out of 100 rating, based on 31 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[18]

Roger Ebert gave the film 3½ stars out of 4, writing that "director E. Elias Merhige and his writer, Steven Katz, do two things at the same time. They make a vampire movie of their own, and they tell a backstage story about the measures that a director will take to realize his vision", and that Dafoe "embodies the Schreck of Nosferatu so uncannily that when real scenes from the silent classic are slipped into the frame, we don't notice a difference."[19] Ebert later awarded the film his Special Jury Prize on his list of "The Best 10 Movies of 2000", writing of Dafoe's "astonishing performance" and of the film, "Avoiding the pitfall of irony; it plays the material straight, which is truly scary."[20]

A. O. Scott of The New York Times wrote, "You can find diversion in an improbable blend of behind-the-scenes satire and art-house fright-fest, anchored by Willem Dafoe's creepy, comical and oddly moving performance as the blood-sucking Schreck."[21]

Awards and nominations[edit]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Willem Dafoe | Nominated | [4] |

| Best Makeup and Hairstyling | Ann Buchanan, Amber Sibley | Nominated | ||

| Bram Stoker Award | Best Screenplay | Steven Katz | Won | [22] |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Willem Dafoe | Nominated | [23] |

| Golden Satellite Awards | Best Supporting Actor, Comedy or Musical | Won | [24] | |

| Independent Spirit Awards | Best Supporting Male | Won | [25] | |

| Best Cinematography | Lou Bogue | Nominated | ||

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Willem Dafoe | Won | [26] |

| Screen Actors Guild Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Nominated | [27] |

See also[edit]

- Vampire films

- "I, the Vampire", a 1937 short story by Henry Kuttner about an ancient European vampire employed as a horror film actor in Hollywood.

- "Flicker", an episode of American Horror Story: Hotel in which Murnau was actually a vampire while filming Nosferatu.

References[edit]

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire (15)". British Board of Film Classification. July 31, 2000. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire Box Office Data". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire (2000)". Box Office Mojo. 5 April 2001. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ a b "The 73rd Academy Awards - 2001". Oscars.org. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Atkinson, Michael (26 January 2001). "The truth about film-maker FW Murnau". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Bonus features on Shadow of the Vampire DVD - Interview with E. Elias Merhige.

- ^ a b Swanson, Tim (2000-10-04). "Hollywood Stock Exchange bows pic view". Variety. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (6 June 1997). "Con Air (1997) Signs and Symbols on a Thrill Ride". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (17 August 1990). "Wild At Heart (1990) Review/Film; In the Eerie Cosmos of David Lynch, Reality Is Reeling". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Magid, Ron (December 2000). "Dark Shadows". American Cinematographer. Vol. 81, no. 12. pp. 68–75. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ Koehler, Robert (December 12, 2000). "Shadow of the Vampire". Variety. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ DiOrio, Carl (2001-06-29). "Lions Gate homing in on profits". Variety. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire - Releases". AllMovie. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Shadow of a Vampire". Amazon. January 5, 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (2000-05-30). "Shadow of the Vampire". Variety. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ Cho, Seongyong (November 4, 2021). "Vampire's Twist: A Look Back at Shadow of the Vampire". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire (2000)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Shadow of the Vampire reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 26, 2001). "Shadow Of The Vampire". rogerebert.com. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 2000). "The Best Movies of 2000". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 2009-12-30. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 29, 2000). "FILM REVIEW; Son of 'Nosferatu,' With a Real-Life Monster". The New York Times.

- ^ "Horror Writers Association - Past Bram Stoker Award Nominees & Winners". horror.org. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 2001". Golden Globes. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "2001 5th Annual SATELLITE™ Awards". International Press Academy. Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "'Tiger' grabs 3 Independent Spirit awards". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. March 26, 2001. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "'Crouching Tiger' Wins Top Prize from L.A. Critics". Los Angeles Times. 2000-12-17. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "7th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". sagawards.org. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

External links[edit]

- 2000 films

- 2000 horror films

- 2000 independent films

- American multilingual films

- American supernatural horror films

- American vampire films

- BBC Film films

- Biographical films about actors

- British supernatural horror films

- British vampire films

- Cultural depictions of actors

- Cultural depictions of film directors

- Cultural depictions of German people

- Dracula films

- English-language Luxembourgian films

- F. W. Murnau

- Films about filmmaking

- Films about films

- Films about snuff films

- Films based on urban legends

- Films directed by E. Elias Merhige

- Films produced by Nicolas Cage

- Films set in 1921

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in castles

- Films set in Czechoslovakia

- Films set in Poland

- Films set in Slovakia

- Films shot in Luxembourg

- 2000s German-language films

- Gothic horror films

- Luxembourgian horror films

- Luxembourgish-language films

- Nosferatu

- Period horror films

- Saturn Films films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- Nosferatu films

- Films scored by Dan Jones