The Other (1972 film)

| The Other | |

|---|---|

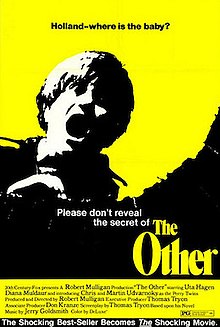

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Mulligan |

| Screenplay by | Thomas Tryon |

| Based on | The Other 1971 novel by Thomas Tryon |

| Produced by | Thomas Tryon Robert Mulligan |

| Starring | Uta Hagen Diana Muldaur Chris Udvarnoky Martin Udvarnoky |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees |

| Edited by | Folmar Blangsted O. Nicholas Brown |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.25 million[2] |

| Box office | $3.5 million (US/ Canada)[3] |

The Other is a 1972 American horror[4] psychological thriller film directed by Robert Mulligan, adapted for film by Thomas Tryon from his 1971 novel of the same name. It stars Uta Hagen, Diana Muldaur, and twins Chris and Martin Udvarnoky, with Victor French, John Ritter, and Jenny Sullivan in supporting roles.

Plot[edit]

In 1935 Connecticut, widow Alexandra Perry lives with her identical twin sons, Holland and Niles, on their family farm, overseen by Uncle George and his wife Vee, along with their bratty son Russell. Residing nearby is their Russian emigrant grandmother Ada, with whom Niles shares a close relationship. Ada has taught Niles to astrally project his mind into the bodies of other living creatures, an ability that runs in the Perry family; they refer to this as "the game". Unfortunately, it's no innocent game, considering it leads to the freak "accidental" death of Cousin Russell, the paralysis of Alexandra, and a fatal heart attack suffered by a neighbor, Mrs. Rowe. Ada now realizes the game is evil, and advises Niles never to play it again. Further, she forces Niles to admit Holland has been dead since their birthday the previous March when he fell down a well, but Niles is unable to accept the truth. Ada realizes that Niles has been using the game to keep his brother alive in his mind, and that it is in fact Niles who is responsible for the summer's tragedies.

Later, Niles' older sister gives birth to a baby girl. Niles adores the child, but "Holland", who is fascinated with the recent kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby, steals the infant. A posse is formed to find the child. But Ada, suspecting the worst, searches the barn for Niles. She discovers him prowling the storage cellar and, speaking to "Holland", demands the whereabouts of the baby. Meantime, the posse finds the baby drowned in a wine cask, and an alcoholic immigrant farmhand is accused of the murder. Informed of the discovery and realizing what has happened, Ada pours kerosene into the cellar and throws herself onto it with a kerosene lamp, causing an inferno that burns the barn down. Months later, the charred remains of the barn are cleared away. It is revealed that Niles escaped the fire due to "Holland" previously cutting the padlock from the cellar door. With Ada dead and his mother a catatonic, paralyzed invalid, no one suspects Niles' secret. In the film's final shot, Niles peers out from his bedroom window while being called downstairs for lunch.

Cast[edit]

- Chris Udvarnoky as Niles Perry

- Martin Udvarnoky as Holland Perry

- Uta Hagen as Ada

- Diana Muldaur as Alexandra Perry

- Norma Connolly as Aunt Vee

- Victor French as Mr. Angelini

- Loretta Leversee as Winnie

- Lou Frizzell as Uncle George

- Clarence Crow as Russell

- John Ritter as Rider

- Jenny Sullivan as Torrie

- Portia Nelson as Mrs. Rowe

- Jack Collins as Mr. Pretty

Production[edit]

Locations[edit]

The film was shot entirely on location in Murphys, California and Angels Camp, California. Director Robert Mulligan had hoped to shoot the film on location in Connecticut, where it takes place, but because it was autumn when the film entered production (and therefore the color of the leaves would not reflect the height of summer, when the story takes place) this idea was dropped. Assistant director/associate producer Don Kranze picked the location for the house in Murphys, having remembered it from the 1947 film The Red House. The fairground sequence was shot in Angels Camp.[5]

Direction[edit]

Mulligan described his intentions with the film: “I want to put the audience into the body of the boy with this shot and to make the experience of the film, from beginning to end, a totally subjective one.” Of the character of Niles, he commented “If Niles could have life just the way he wanted it, his world would contain only Ada, Holland, and himself—preferably only Holland and himself." Of the character of Ada, he said “She was the heart of the house. She has a primitive sense of imagination and drama, which is the greatest thing an adult can give a child ... Her only failing is that she has a maternal love so strong that it blinds her to what is happening. Though she enriches and turns on the child’s imagination, her gift is used in a destructive way by the child.”[6]

Cast[edit]

Mulligan and Tryon pursued Uta Hagen for the role of Ada; Tryon and his then-lover, Clive Clerk, allegedly had to first convince Mulligan that Hagen was right for the part. Mulligan then visited Hagen at her house in Montauk and convinced her to take the role. Tryon specifically asked for Diana Muldaur to play the part of Alexandra, because she reminded him of his own mother. Tryon later stated that although he was happy with the performances by Hagen and the Udvarnoky twins, he was displeased with some of the other casting decisions. Assistant director Don Kranze later recalled that Tryon did not approve of Lou Frizzell in the role of Uncle George, since Frizzell's Southern accdent didn't quite fit the New England origins of the character. [7]

Chris and Martin Udvarnoky auditioned for the roles of Niles and Holland after a grade-school teacher informed their parents about the production. After they were cast, the boys met with Robert Mulligan, who asked them which boy wanted to play Niles and which boy wanted to play Holland; he then gave both boys the roles that they each asked for. In an interview for the video essay The Making of The Other, Martin Udvarnoky recalls that Mulligan was mostly a nice director on the set, but that he got a little angry during the filming of a (deleted) swimming scene where the boys were struggling to act due to the cold outdoor weather.[8]

Mulligan never shows the brothers in frame together. They are always separated by a camera pan or an editing cut.

John Ritter made one of his early appearances in the film as the boys' brother-in-law Rider Gannon. Decades later, on an episode of 8 Simple Rules for Dating My Teenage Daughter, Ritter paid tribute to Robert Mulligan in a scene where his character quoted To Kill a Mockingbird.[9]

Music[edit]

Goldsmith's compositions for the film can be heard in a 22-minute suite found on the soundtrack album of The Mephisto Waltz. This CD was released 25 years after the release of the film. Due to feedback from test screenings, the film was shortened, and much of Goldsmith's music was taken out.[10]

Alternate ending[edit]

When the film aired on CBS in the 1970s, the final shot replaces Winnie's line with a voiceover by Niles: "Holland, the game's over. We can't play the game anymore. But when the sheriff comes, I'll ask him if we can play it in our new home." The voiceover is dubbed by a different child than the actor and may have been edited into the television version to imply that Niles had not gotten away with murder, but was waiting to be taken to a mental health care facility. All subsequent media releases and television broadcasts omit this voiceover in favor of the original theatrical ending.

Reception[edit]

The film experienced a quiet theatrical run, but it had regular television airings in the late 1970s. Among the film's admirers was Roger Ebert, who wrote in his review, the movie "has been criticized in some quarters because Mulligan made it too beautiful, they say, and too nostalgic. Not at all. His colors are rich and deep and dark, chocolatey browns and bloody reds; they aren't beautiful but perverse and menacing. And the farm isn't seen with a warm nostalgia, but with a remembrance that it is haunted."[11] After Chris Udvarnoky's death on October 25, 2010,[12] Ebert paid tribute to Udvarnoky on his Twitter page.[13]

Tom Tryon, however, was disappointed with the film, despite having written the screenplay. When asked about the film in a 1977 interview, Tryon recalled "Oh, no. That broke my heart. Jesus. That was very sad...That picture was ruined in the cutting and the casting. The boys were good; Uta was good; the other parts, I think, were carelessly cast in some instances--not all, but in some instances. And, God knows, it was badly cut and faultily directed. Perhaps the whole thing was the rotten screenplay, I don't know. But I think it was a good screenplay."

In the same interview, Tryon also hinted that he initially had been considered to direct the film before Mulligan was hired for the job: "It was all step-by-step up to the point of whether I was going to become a director or not. The picture got done mainly because the director who did it wanted to do that property, and he was a known director; he was a known commodity."[14]

Legacy[edit]

After The Other, Chris and Martin Udvarnoky did some stage work with Uta Hagen, and they both tried out for the lead role in 1973's Tom Sawyer, but neither got the part. Ultimately, they both decided not to pursue careers acting in movies, partially because they were disturbed by the attention which they received from fans when The Other premiered, and also because they preferred to resume normal childhoods.[15]

Chris Udvarnoky became an emergency medical technician. He died of kidney disease in Elizabeth, New Jersey on October 25, 2010 at the age of 49.[16]

In an interview for the video essay The Making of The Other, Martin Udvarnoky has reflected that The Other "is the kind of movie that either you love, or you don't."[17]

See also[edit]

- List of American films of 1972

- A Tale of Two Sisters (2003)

- The Uninvited (2009)

- The Uninvited (1944)

- Goodnight, Mommy (2014)

- The Good Son (1993)

- The Corsican Brothers (1941)

References[edit]

- ^ "The Other". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020.

- ^ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p256

- ^ Solomon p 232. Please note figures are rentals not total gross.

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth (2007). Horror Films of the 1970s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-786-49156-8.

- ^ "The Making of THE OTHER (1972) - memories relayed by Don Kranze"

- ^ "您的訪問出錯了-404頁面".

- ^ "The Making of THE OTHER (1972) - memories relayed by Diana Muldaur, Don Kranze and C. Robert Holloway"

- ^ "The Making of THE OTHER (1972) - memories relayed by Martin Udvarnoky"

- ^ A Tribute to Robert Mulligan. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11.

- ^ a b c Dahlin 1977, p. 263

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 6, 1972). "The Other". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015.

- ^ Obituaries & Guestbooks from The Star-Ledger

- ^ "Ebertchicago". Twitter.

- ^ ^ a b c Dahlin 1977, p. 263

- ^ "The Making of THE OTHER (1972) - memories relayed by Martin Udvarnoky"

- ^ https://www.fanwoodmemorial.com/obituaries/Christopher-Udvarnoky?obId=4492143

- ^ "The Making of THE OTHER (1972) - memories relayed by Martin Udvarnoky"

Bibliography[edit]

- Dahlin, Robert (1977). Conversations With Writers. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Company. ISBN 0-8103-0943-2.

External links[edit]

- 1972 films

- 1972 horror films

- 1970s mystery films

- 1970s psychological thriller films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Films set in 1935

- Films set in Connecticut

- American ghost films

- American mystery films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films about twin brothers

- Films directed by Robert Mulligan

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films based on American horror novels

- 1970s American films