Pyruvate kinase deficiency

| Pyruvate kinase deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency[1] |

| |

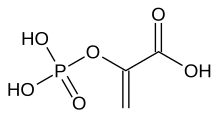

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Anemia, tachycardia[2] |

| Causes | Mutation in PKLR gene[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical exam, CBC[4] |

| Treatment | Blood transfusion[4] |

Pyruvate kinase deficiency is an inherited metabolic disorder of the enzyme pyruvate kinase which affects the survival of red blood cells.[4][5] Both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance have been observed with the disorder; classically, and more commonly, the inheritance is autosomal recessive. Pyruvate kinase deficiency is the second most common cause of enzyme-deficient hemolytic anemia, following G6PD deficiency.[6]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Symptoms can be extremely varied among those suffering from pyruvate kinase deficiency. The majority of those suffering from the disease are detected at birth while some only present symptoms during times of great physiological stress such as pregnancy, or with acute illnesses (viral disorders).[7] Symptoms are limited to or most severe during childhood.[8] Among the symptoms of pyruvate kinase deficiency are:[2]

- Mild to severe hemolytic Anemia

- Cholecystolithiasis

- Tachycardia

- Hemochromatosis

- Icteric sclera

- Splenomegaly

- Leg ulcers

- Jaundice

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

The level of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate is elevated: 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, a precursor of phosphoenolpyruvate which is the substrate for Pyruvate kinase, is increased and so the Luebering-Rapoport pathway is overactivated. This led to a rightward shift in the oxygen dissociation curve of hemoglobin (i.e. it decreases the hemoglobin affinity for oxygen): In consequence, patients may tolerate anemia surprisingly well.[9]

Cause[edit]

Pyruvate kinase deficiency is due to a mutation in the PKLR gene. There are four pyruvate kinase isoenzymes, two of which are encoded by the PKLR gene (isoenzymes L and R, which are used in the liver and erythrocytes, respectively). Mutations in the PKLR gene therefore cause a deficiency in the pyruvate kinase enzyme.[3][10]

180 different mutations have been found on the gene coding for the L and R isoenzymes, 124 of which are single-nucleotide missense mutations.[11] Pyruvate kinase deficiency is most commonly an autosomal recessive trait.[12] Although it is mostly homozygotes that demonstrate symptoms of the disorder,[2] compound heterozygotes can also show clinical signs.[11]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Pyruvate kinase is the last enzyme involved in the glycolytic process, transferring the phosphate group from phosphenol pyruvate to a waiting adenosine diphosphate (ADP) molecule, resulting in both adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and pyruvate. This is the second ATP producing step of the process and the third regulatory reaction.[7][13] Pyruvate kinase deficiency in the red blood cells results in an inadequate amount of or complete lack of the enzyme, blocking the completion of the glycolytic pathway. Therefore, all products past the block would be deficient in the red blood cell. These products include ATP and pyruvate.[2]

Mature erythrocytes lack a nucleus and mitochondria. Without a nucleus, they lack the ability to synthesize new proteins so if anything happens to their pyruvate kinase, they are unable to generate replacement enzymes throughout the rest of their life cycle. Without mitochondria, erythrocytes are heavily dependent on the anaerobic generation of ATP during glycolysis for nearly all of their energy requirements.[14]

With insufficient ATP in an erythrocyte, all active processes in the cell come to a halt. Sodium potassium ATPase pumps are the first to stop. Since the cell membrane is more permeable to potassium than sodium, potassium leaks out. Intracellular fluid becomes hypotonic, water moves down its concentration gradient out of the cell. The cell shrinks and cellular death occurs, this is called 'dehydration at cellular level'.[2][15][16] This is how a deficiency in pyruvate kinase results in hemolytic anaemia, the body is deficient in red blood cells as they are destroyed by lack of ATP at a larger rate than they are being created.[17]

Diagnosis[edit]

The diagnosis of pyruvate kinase deficiency can be done by full blood counts (differential blood counts) and reticulocyte counts.[18] Other methods include direct enzyme assays, which can determine pyruvate kinase levels in erythrocytes separated by density centrifugation, as well as direct DNA sequencing. For the most part when dealing with pyruvate kinase deficiency, these two diagnostic techniques are complementary to each other as they both contain their own flaws. Direct enzyme assays can diagnose the disorder and molecular testing confirms the diagnosis or vice versa.[6] Furthermore, tests to determine bile salts (bilirubin) can be used to see whether the gall bladder has been compromised.[18]

Treatment[edit]

Most affected individuals with pyruvate kinase deficiency do not require treatment. Those individuals who are more severely affected may die in utero of anemia or may require intensive treatment. With these severe cases of pyruvate kinase deficiency in red blood cells, treatment is the only option, there is no cure. However, treatment is usually effective in reducing the severity of the symptoms.[13][19]

The most common treatment is blood transfusions, especially in infants and young children. This is done if the red blood cell count has fallen to a critical level.[12] The transplantation of bone marrow has also been conducted as a treatment option.[10]

There is a natural way the body tries to treat this disease. It increases the erythrocyte production (reticulocytosis) because reticulocytes are immature red blood cells that still contain mitochondria and so can produce ATP via oxidative phosphorylation.[14] Therefore, a treatment option in extremely severe cases is to perform a splenectomy. This does not stop the destruction of erythrocytes but it does help increase the amount of reticulocytes in the body since most of the hemolysis occurs when the reticulocytes are trapped in the hypoxic environment of the spleen. This reduces severe anemia and the need for blood transfusions.[8]

Mitapivat was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2022.[20]

Epidemiology[edit]

Pyruvate kinase deficiency happens worldwide, however northern Europe, and Japan have many cases. The prevalence of pyruvate kinase deficiency is around 51 cases per million in the population (via gene frequency).[13][21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 266200

- ^ a b c d e "Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency Clinical Presentation: History and Physical Examination". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ a b "Pyruvate kinase deficiency". Genetics Home Reference. 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ a b c "Pyruvate kinase deficiency: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ "Pyruvate kinase deficiency | Disease | Overview | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Patrick G.; Glader, Bertil (2016-05-01). "Diagnosis of Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 63 (5): 771–772. doi:10.1002/pbc.25922. ISSN 1545-5017. PMID 26836632. S2CID 42964783.

- ^ a b Gordon-Smith, E.C. (1974). "Pyruvate kinase deficiency". Journal of Clinical Pathology. s3-8 (1): 128–133. doi:10.1136/jcp.27.suppl_8.128. PMC 1347209. PMID 4536359.

- ^ a b "Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 2016-08-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ al.], Ronald (2013). Hematology basic principles and practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 703. ISBN 9781455740413.

- ^ a b Zanella, Alberto; Fermo, Elisa; Bianchi, Paola; Valentini, Giovanna (2005-07-01). "Red cell pyruvate kinase deficiency: molecular and clinical aspects". British Journal of Haematology. 130 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05527.x. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 15982340.

- ^ a b Christensen, Robert D.; Yaish, Hassan M.; Johnson, Charlotte B.; Bianchi, Paola; Zanella, Alberto (October 2011). "Six Children with Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency from One Small Town: Molecular Characterization of the PK-LR Gene". The Journal of Pediatrics. 159 (4): 695–697. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.043. PMID 21784452.

- ^ a b Zanella, A.; Bianchi, P.; Fermo, E. (2007-06-01). "Pyruvate kinase deficiency". Haematologica. 92 (6): 721–723. doi:10.3324/haematol.11469. ISSN 0390-6078. PMID 17550841.

- ^ a b c "Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency. Information about PKD | Patient". Patient. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ a b Wijk, Richard van; Solinge, Wouter W. van (2005-12-15). "The energy-less red blood cell is lost: erythrocyte enzyme abnormalities of glycolysis". Blood. 106 (13): 4034–4042. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-04-1622. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 16051738.

- ^ "Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 2018-08-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Haematology Made Easy. AuthorHouse. 2013-02-06. p. 181. ISBN 9781477246511.

- ^ Jacobasch, Gisela; Rapoport, Samuel M. (1996-04-01). "Chapter 3 Hemolytic anemias due to erythrocyte enzyme deficiencies". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 17 (2): 143–170. doi:10.1016/0098-2997(96)88345-2. PMID 8813716.

- ^ a b Disorders, National Organization for Rare (2003-01-01). NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 496. ISBN 9780781730631.

- ^ Davey, Patrick (2010-02-01). Medicine at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons. p. 341. ISBN 9781405186162.

- ^ "Agios Announces FDA Approval of Pyrukynd (mitapivat) as First Disease-Modifying Therapy for Hemolytic Anemia in Adults with Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency" (Press release). Agios Pharmaceuticals. 17 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ Beutler, Ernest; Gelbart, Terri (2000). "Estimating the prevalence of pyruvate kinase deficiency from the gene frequency in the general white population" (PDF). Blood. 95 (11): 3585–3588. doi:10.1182/blood.V95.11.3585. PMID 10828047. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

Further reading[edit]

- Hoffman, Ronald; Benz, Edward J. Jr.; Silberstein, Leslie E.; Heslop, Helen; Weitz, Jeffrey; Anastasi, John (2013-02-12). Hematology: Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1455776887.

- Baroncian, Luciano (1994). "Prenatal Diagnosis of Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency". Blood. 84 (7): 2354–2356. doi:10.1182/blood.V84.7.2354.2354. PMID 7919353.