Non-price competition

Non-price competition is a marketing strategy "in which one firm tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of attributes like design and workmanship".[1] It often occurs in imperfectly competitive markets because it exists between two or more producers that sell goods and services at the same prices but compete to increase their respective market shares through non-price measures such as marketing schemes and greater quality.[2] It is a form of competition that requires firms to focus on product differentiation instead of pricing strategies among competitors. Such differentiation measures allowing for firms to distinguish themselves, and their products from competitors, may include, offering superb quality of service, extensive distribution, customer focus, or any sustainable competitive advantage other than price. When price controls are not present, the set of competitive equilibria naturally correspond to the state of natural outcomes in Hatfield and Milgrom's two-sided matching with contracts model.[3][4]

It can be contrasted with price competition, which is where a company tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of low price. Non-price competition typically involves promotional expenditures (such as advertising, selling staff, the locations convenience, sales promotions, coupons, special orders, or free gifts), marketing research, new product development, and brand management costs.

Businesses can also decide to compete against each other in the form of non-price competition such as advertising and product development. Oligopolistic businesses normally do not engage in price competition as this usually leads to a decrease in the profit businesses can make in that specific market.

Non-price competition is a key strategy in a growing number of marketplaces (oDesk, TaskRabbit, Fiverr, AirBnB, mechanical turk, etc) whose sellers offer their Service as a product, and where the price differences are virtually negligible when compared to other sellers of similar productized services on the same marketplaces. They tend to distinguish themselves in terms of quality, delivery time (speed), and customer satisfaction, among other things.

Market structure[edit]

Although any company can use a non-price competition strategy, it is most common among oligopolies and monopolistic competition, because firms can be extremely competitive. Firms will engage in non-price competition, in spite of the additional costs involved, because it is usually more profitable than selling for a lower price, and avoids the risk of a price war.

Oligopolistic competition[edit]

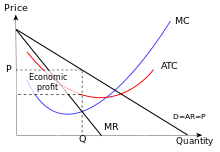

Non-price competition often occurs in oligopoly, where few firms dominate the market. Due to the little or few firms in the market, these firms tend to compete in non-price measures to distinguish themselves. Such competition would be otherwise known as quality competition where oligopolistic firms depend on their quality improvement intensities to survive.[5] In order to distinguish themselves well, These firms can compete in price, but more often, oligopolistic firms engage in non-price competition because of their kinked demand curve. In the kinked demand curve model, the firm will maximize its profits at Q,P where the marginal revenue (MR) is equal to the marginal cost (MC) of the firm. Hence, a change in MC would not necessarily change the market price, implying rather stable and sticky market prices.

Monopolistic competition[edit]

Monopolistic market structures also engage in non-price competition because they are not price takers. Due to having rather fixed market prices, leading to inelastic demand, they engage in product differentiation. Monopolistic markets engage in non-price competition because of how the market is designed where the firm dominates the market. In order to sustain in the market, they have to innovate and improve on their product development to appeal to consumers. The new trade theory suggests that the model of monopolistic competition plays a big role in explaining trade trends in trade patterns where product development drives product differentiation. Under monopolistic competition, firms engage in non-price competition to innovate and further boost their brand image.

Main types[edit]

There are two main branches of non-price competition. This is where firms branch out to create new avenues for themselves to remain competitive in a market where prices are rather sticky. Such streams of non-price competition include product differentiation and/or development and advertising and/or promotion.

Product differentiation[edit]

Product differentiation allows for a firm to establish its products from its competitors to win over a greater market share. The more different the products of rival firms are, the lower the cross effects between their markets with regards to both non-price and price variables.[6] By offering a wide range of products, firms can not only achieve economies of scope, but also be able to expand their market base. However, such product differentiation measures may result in significantly higher overhead costs.

Advertising and promotion[edit]

Promotion can be considered an umbrella term to include all advertising, branding, public relations and packaging. This strategy includes all aspects of non-price strategies to continuously capture market attention. Advertising is divided into two categories:

- Informative: This form of advertising includes informing consumers about product features, details descriptions.[1]

- Persuasive: This form of advertising engages with the consumers on an emotional level. Such advertising methods are highly linked to behavioural economics which takes advantage of the heuristics and bounded rationality of consumers when making decisions.

Advertising mediums can be designed specifically to meet with the expectations of consumers as well as the size of the market. Firms aim on reaching as high targets as possible by making use of the network effects of advertising.[6]

Promotional means depend on a number of factors such as the nicheness of the market, and allocated promotional budgets.

Examples[edit]

There are many ways of how firms can engage in non-price competition to increase their market share and retain their customer base. Examples are such like loyalty programs, subsidized delivery, unique selling points, brand recognition, ethical and/or charitable concerns, after-sales service, positive feedback reviews, marketing campaigns and many more. The few of the more important and common examples of non-price competition are as follows.

Loyalty programs[edit]

Most firms offer out loyalty cards in order to capture market attention and retain customers. Loyalty cards are a form of differentiation where customers are given incentives to purchase from that specific firm.

Subsidized delivery[edit]

Big firms such as Amazon has been successful in offering AmazonPrime delivery in order to provide free delivery for their customers, with a paid subscription. This would give customers an incentive to purchase more because of the waived delivery fee. This works especially well for customers who are regular online shoppers. Supermarkets such as Tesco and Costco are offering delivery services worldwide as well, to cater for their international customer bases.

Unique selling points[edit]

Firms with unique selling points are a result of focused differentiation because products are customized to consumer preferences. For instance, food companies now engage in promoting health foods which cater to healthy-living which has become a norm nowadays. Such products can have gluten-free options, sugar-free options and even low-carb alternatives. Some unique selling points might also be a result of good packaging that aim to capture consumer attention.

Accumulation of positive reviews[edit]

Many large companies rely on positive reviews from previous customers in order to gain positive feedback from others.[7] Such methods are important because it gives other new consumers an anchor to base the quality of their products on, and creates a certain level of trust from the amount of positive feedback received.

Offering good after-sales service[edit]

After-sales service is crucial for the reputation and brand loyalty of the firm. In order to retain customers, they would have to provide great after-sales service so customers would be able to return and obtain the services they demand. Examples are such like Apple Care offering warranty and also proper services to repair the purchased devices.

Relationship with excess profits[edit]

Many economists wonder about the literature on non-price competition whether positive profits accruing to the members of an oligopolistic group of firms, which may be pushed to zero by competitive price undercutting, can also be competed away by advertising or other non-price activities.[6] This question is specifically relevant to regulated industries without free entry, or a cartel arrangement, where the objective of the price regulation is to preserve profit levels. This also comes to the question regarding successful or unsuccessful product differentiation among competitors. If advertising costs are higher than the revenues of the firms, then it would lead to a waste of resources, resulting in negative profits.[8]

The history of price competition has led to many believing that non-price competition is less intense as compared to price competition. Formal models like those of Stigler(1968) show that the outcome depends on how the system parameters is valued.[6]

Differences with price competition[edit]

The main difference between price competition and non-price competition would be the traditional case of which price competition exists in homogenous products where products are very difficult to be differentiated and can only be produced in minimal forms. Such circumstances would result in firms competing with prices, leading to price wars. Price competition exists as a result of balancing between supply and demand for specified goods.[9]

Non-price competition engages in any other forms of non-price attributes of products or services tailored to capture as much market share as possible. Non-price competition revolve around competing qualitatively among products and services.

With relations to the demand curve, price competition implies that the firm accepts its demand curve and manipulates its price to reach its goals. Non-price competition however, seeks to change its demographics and shape of the demand curve by adapting and innovating.

Incentives[edit]

Price regulation[edit]

Price competition can be completely absent in markets where the government fully sets the rates.[10] When there is no room for price competition because of fixed market prices, firms resort to other non-price alternatives to compete. Before deregulation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were many industries in the United States where price regulation was done in conjunction with non-price competition but disguised as price competition.[11] The fixing of commission rates by the New York Exchange still allows brokerage houses to compete through non-price measures through offering advisory services regarding investments.[11] However, elimination of price competition through regulation does not necessarily result in non-price competition. In an initially unregulated industry, firms would be able to choose optimal values for both price and non-price values.[11] Such an incentive would only happen when prices are regulated at a different equilibrium level.

Acts of collusion/cartel agreements[edit]

When firms within an industry engage in collusions or cartels to fix the market prices of their products, this rules out price competition among them. This would give each firm a fixed share of total output at the common price, therefore, showing a negatively-sloping demand curve. Under a collusion, firms conspire against the consumer, but still compete among each other in terms of quality or by advertising.[12] This is also to maintain their own branding by colluding on a set price so their brands can be the distinguishing factor within a branding competition.[13]

Consider a situation where the cartel fixes a price and allows for competition in advertising. There would be two marginal costs: (i) Marginal cost of production alone (MCp) and (ii) Marginal cost of production + advertising (MCp+a). This leads to two possibilities: (1) Marginal cost (MCp+a) stays constant, (2) Marginal cost (MCp+a) falls. If marginal production cost (MCp) is constant, the marginal production cost+cost of advertisement (MCp+a) will remain constant as well, under the conditions of increasing returns to advertising. On the other hand, if marginal production cost is rising, then the rise must be equally offset by increasing returns to advertising. In case (1), each firm will seek to expand output by increasing advertising efforts. In case (2), firms will expand until where (MCp+a) equals to the price.

Price competition is believed by most economists to be more effective in increasing output and reducing profits as compared to non-price competition. However, marginal costs of production do not rise as rapidly as marginal costs of advertising, quality and other non-price variables. Therefore, the more common and plausible view would be that the marginal non-price variable cost is larger than the marginal price-reduction cost, if the firm was an initial monopolist.[11]

Cases involving joint ventures[edit]

When an industry is dominated by joint ventures, this makes joint venture partners obtain majority of the market power. This results in an irrelevant price competition because it would not be of use. An example would be the Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585 (1985) where these two firms owning these mountains formed a joint venture to offer consumers a lift ticket good at all four areas. Although they were not engaging in price competition, this joint venture was structured in a way where non-price competition was fostered because the firms shared the revenue, and which allowed consumers to still be able to make their own choices in terms of the quality of the facilities offered by both partners.

Involvement of third-party payors[edit]

When consumers' bills are paid by third party entities, the consumer will decide on their consumption based on non-price measures, such as quality, service or location. For instance, insurance coverage allow for buyers to engage in non-price decision making because they know that the insurance company will pay for them based on the insurance package they signed up for.

Antitrust Law and non-price competition[edit]

With relations to the above section regarding incentives to engage in non-price competition, these incentives lead to an unfair market structure that require the attention of competition regulators, specifically under Antitrust Laws.[10] For cases with price regulation, antitrust policies have managed to prevent various firms within the airline industry from merging so they would still engage in non-price competition.

For cases involving industry-wide joint ventures, courts have paid a close attention to only permit firms to engage in joint ventures if they are still engaging in non-price competition that protects the choices of consumers.

For cases involving third-party payors, partial solutions where consumers are forced to engage in some price comparisons where a threat of rate increases if too many claims are made.

Advantages and significance[edit]

Non-price competition is significant in the wide areas of economics, business and legal.

Economics[edit]

As non-price competition consistently brings about product differentiation especially among monopolistic firms, it brings about a greater diversity in product offerings, and can benefit and increase consumer utility through various ways. Non-price effects increasingly capture attention in the economics domain of on the different dimensions and effects of non-price competition in the form of variety, quality and service.[14]

Business[edit]

Business research confirms that firms rely highly on non-price strategies in competition. For example, in strategic management, areas of focus revolve around continuous innovation, synergism and long-term relationships that build sustainable businesses.[14] Similarly, in marketing, price is not only the only factor that affects the firm. Other areas need to complement the prices set by firms in order to maintain market presence. These areas may include the 4 P's: Product, Promotion, Place and Price.

Law/legal[edit]

The existence of non-price competition call upon the attention of antitrust law regulators in order to maintain fair competition among firms. A significant issue in the Continental Can litigation was how a relevant product market should be known for reviewing company mergers.[14]

Other advantages[edit]

- Innovation within the companies and industry: sales tactics, social media posts, virtual/technological advertisements, direct sales

- Quality assurance and improvement

- Brand establishment and reputation

- Economies of scope: offering products and services to various demographics.

- Healthier competition among competitors where they go beyond their status quo to achieve competitive advantage within the industry.

- Widening consumer choices: they get to select based on non-price attributes of products.

- Opens up avenues to different industries as more cooperation is needed within industries to innovate.

Disadvantages[edit]

- Time-lapse: customers take time to notice the changes within the industry.[15]

- May incur additional costs to firms engaging in non-price competition (advertising, marketing, etc.)

- Greater research and development needed.

- Information asymmetry among customers and competitors.

- Moral hazard: consumers are unsure of which firm offers truly better quality products.

- Might lead to wasteful rent-seeking: If industry output does not increase, advertising is considered unambiguously to be wasteful.[8]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ McConnell, Campbell R. (2002). Economics : principles, problems, and policies. Brue, Stanley L., 1945- (15th ed.). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-234036-3. OCLC 47074801.

- ^ A dictionary of business and management. Law, Jonathan (Sixth ed.). Oxford. 2016. ISBN 978-0-19-176527-8. OCLC 944122322.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Hatfield, John William; Kojima, Fuhito (2008). "Matching with Contracts: Comment". The American Economic Review. 98 (3): 1189–1194. doi:10.1257/aer.98.3.1189. ISSN 0002-8282. JSTOR 29730113.

- ^ Hatfield, John William; Milgrom, Paul R (2005-08-01). "Matching with Contracts" (PDF). American Economic Review. 95 (4): 913–935. doi:10.1257/0002828054825466. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Moghadam, Hamed Markazi (2020-04-01). "Price and non-price competition in an oligopoly: an analysis of relative payoff maximizers". Journal of Evolutionary Economics. 30 (2): 507–521. doi:10.1007/s00191-019-00653-8. hdl:10419/119460. ISSN 1432-1386. S2CID 214032844.

- ^ a b c d Lancaster, K. J. (2016), "Non-price Competition", The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–4, doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1739-1, ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5, retrieved 2020-11-01

- ^ Pettinger, Tejvan (9 December 2019). "Non-Price Competition". Economics Help. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ a b Boudreaux, Donald J. (1989). "Imperfectly Competitive Firms, Non-Price Competition, and Rent Seeking". Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft. 145 (4): 597–612. ISSN 0932-4569. JSTOR 40751243.

- ^ "Price and non-price competition". CEOpedia | Management online. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ a b "Using the "Consumer Choice" Approach to Antitrust Law". Antitrust Law Journal. 74: 175–264 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Stigler, George J. (1968). "Price and Non-Price Competition". Journal of Political Economy. 76 (1): 149–154. doi:10.1086/259391. ISSN 0022-3808. JSTOR 1830736. S2CID 154265215.

- ^ "Price Fixing and Non-Price Competition". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ Wang, Huaqing; Gurnani, Haresh; Erkoc, Murat (2016). "Entry Deterrence of Capacitated Competition Using Price and Non-Price Strategies". Production and Operations Management. 25 (4): 719–735. doi:10.1111/poms.12500. ISSN 1937-5956.

- ^ a b c "Non-Price Effects of Mergers: Introduction and Overview | Request PDF". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "What is Non-Price Competition? Definition and meaning". Market Business News. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

Further reading[edit]

- Brue, Stanleye L., and McConnell, Campbell R. Economics–Principles, Problems and Policies (15th edition). Boston: Irvin/McGraw-Hill, 2002.