Longinus

Longinus | |

|---|---|

Statue of Saint Longinus by Bernini in Saint Peter's Basilica | |

| Born | 1st century in Sandiale or Sandrales[1] of Cappadocia[2] |

| Died | 1st century |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodoxy Catholic Church |

| Major shrine | Inside St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Military attire, lance[3] |

Longinus (/lɒnˈdʒaɪnəs/) is the name given to the unnamed Roman soldier who pierced the side of Jesus with a lance; who in medieval and some modern Christian traditions is described as a convert to Christianity.[4] His name first appeared in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus.[5] The lance is called in Christianity the "Holy Lance" (lancea) and the story is related in the Gospel of John during the Crucifixion.[6] This act is said to have created the last of the Five Holy Wounds of Christ.

This person, unnamed in the Gospels, is further identified in some versions of the legend as the centurion present at the Crucifixion, who said that Jesus was the son of God,[7] so he is considered as one of the first Christians and Roman converts. Longinus' legend grew over the years to the point that he was said to have converted to Christianity after the Crucifixion, and he is traditionally venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, and several other Christian communions.

Origins of the story[edit]

No name for this soldier is given in the canonical Gospels; the name Longinus is instead found in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Longinus was not originally a saint in Christian tradition. An early tradition, found in a sixth or seventh century pseudepigraphal "Letter of Herod to Pilate", claims that Longinus suffered for having pierced Jesus, and that he was condemned to a cave where every night a lion came and mauled him until dawn, after which his body healed back to normal, in a pattern that would repeat until the end of time.[8] Later traditions turned him into a Christian convert, but as Sabine Baring-Gould observed: "The name of Longinus was not known to the Greeks previous to the patriarch Germanus, in 715. It was introduced among the Westerns from the Apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. There is no reliable authority for the Acts and martyrdom of this saint."[7]

The name is probably Latinized from the Greek logchē (λόγχη), the word used for the spear mentioned in John 19:34.[9] It first appears lettered on an illumination of the Crucifixion beside the figure of the soldier holding a spear, written, perhaps contemporaneously, in horizontal Greek letters, LOGINOS (ΛΟΓΙΝΟϹ), in the Syriac gospel manuscript illuminated by a certain Rabulas in the year 586, in the Laurentian Library, Florence. The spear used is known as the Holy Lance, and more recently, especially in occult circles, as the "Spear of Destiny", which was revered at Jerusalem by the sixth century, although neither the centurion nor the name "Longinus" were invoked in any surviving report. As the "Lance of Longinus", the spear figures in the legends of the Holy Grail.[citation needed]

Blindness or other eye problems are not mentioned until after the tenth century.[10] Petrus Comestor was one of the first to add an eyesight problem to the legend and his text can be translated as "blind", "dim-sighted" or "weak-sighted". The Golden Legend says that he saw celestial signs before conversion and that his eye problems might have been caused by illness or age.[11] The touch of Jesus's blood cures his eye problem:

Christian legend has it that Longinus was a blind Roman centurion who thrust the spear into Christ's side at the crucifixion. Some of Jesus's blood fell upon his eyes and he was healed. Upon this miracle Longinus believed in Jesus.[12]

The body of Longinus is said to have been lost twice, and that its second recovery was at Mantua in 1304, together with the Holy Sponge stained with Christ's blood, wherewith it was told—extending Longinus' role—that Longinus had assisted in cleansing Christ's body when it was taken down from the cross. The relic, corpules of alleged blood taken from the Holy Lance, enjoyed a revived cult in late 13th century Bologna under the combined impetus of the Grail romances, the local tradition of eucharistic miracles, the chapel consecrated to Longinus, the Holy Blood in the Benedictine monastery church of Sant'Andrea,[citation needed] and the patronage of the Bonacolsi.[citation needed]

The relics are said to have been divided and then distributed to Prague (St. Peter and Paul Basilica, Vyšehrad)[13] and elsewhere, with the body taken to the Basilica of Sant'Agostino in Rome. However, official guides of the Basilica do not mention the presence of any tomb associated with Saint Longinus.[citation needed] It is also said that the body of Longinus was found in Sardinia;[citation needed] Greek sources assert that he suffered martyrdom in Gabala, Cappadocia.[citation needed]

Present-day veneration[edit]

Longinus is venerated, generally as a martyr, in the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Armenian Apostolic Church. His feast day is kept on 16 October in the Roman Martyrology, which mentions him, without any indication of martyrdom, in the following terms: "At Jerusalem, commemoration of Saint Longinus, who is venerated as the soldier opening the side of the crucified Lord with a lance".[14] The pre-1969 feast day in the Roman Rite is 15 March. The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates him on 16 October. In the Armenian Apostolic Church, his feast is commemorated on 22 October.[15]

The statue of Saint Longinus, sculpted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is one of four in the niches beneath the dome of Saint Peter's Basilica, Vatican City. A spearpoint fragment said to be from the Holy Lance is also conserved in the Basilica.

Longinus and his legend are the subject of the Moriones Festival held during Holy Week on the island of Marinduque, the Philippines.

Hagiographical fragments on St. Longinus from 11th–13th century found in Dubrovnik indicate his veneration in this area in Middle Ages.[16] There is altarpiece St. Longinus and St. Gaudentius by anonymus author from 17th century in St. Anthony the Great Catholic parish church in Veli Lošinj.[17][18]

Brazil[edit]

Folkloric role[edit]

In Brazil, Saint Longinus – in Portuguese, São Longuinho – is attributed the power of finding missing objects. The saint's aid is summoned by the chant:

São Longuinho, São Longuinho, se eu achar [missing object], dou três pulinhos!

(O Saint Longinus, Saint Longinus, if I find [missing object], I'll hop three times!)

Folk tradition explains the association with missing objects with a tale from the saint's days in Rome. It is said he was of short stature and, as such, had unimpeded view of the underside of tables in crowded parties. Due to this, he would find and return objects dropped on the ground by the other attendants.[19]

Accounts vary regarding the promised offering of three hops, citing either deference to an alleged limping of the saint or a plea to the Holy Trinity.[20]

Brazilian spiritism[edit]

Brazilian medium Chico Xavier wrote Brasil, Coração do Mundo, Pátria do Evangelho, a psychographic book of authorship attributed to the spirit of Humberto de Campos. In the book, Saint Longinus is claimed to have been reincarnated as Pedro II, the last Brazilian emperor.[21]

Gallery[edit]

-

Longinus depicted in the Nea Moni Church, Chios, Greece

-

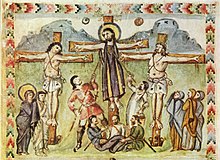

Christ on the Cross, the three Marys, John the Evangelist, and Saint Longinus

-

Saint Longinus in Bom Jesus do Monte, Portugal

-

Fresco in Basilica of St Peter and St Paul in Vyšehrad (Prague).

-

First Class Bone Relic of St. Longinus

-

Longinus in The Crucifixion of Jan Provoost (Groeningmuseum of Bruges)

See also[edit]

- List of names for the Biblical nameless

- Moriones Festival

- Wandering Jew, a figure with whom he is sometimes identified

References[edit]

- ^ "Sandrales/Sandiale: A Pleiades place resource". 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Pago autem nomen est Sandiale" "Σανδιάλη τῇ κώμῃ τό ὃνομα" from «month March» ΙΑ' page. 41 (in pdf page 17). Archived 1 Jul 2016. Retrieved 6 Feb. 2018

- ^ Stracke, Richard (2015-10-20). "Saint Longinus". Christian Iconography.

- ^ Fuhrmann, Christopher (11 April 2014). Policing the Roman Empire: Soldiers, Administration, and Public Order (Reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0199360017.

- ^ Barber, Richard (2004). The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief. Harvard University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780674013902. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

gospel of nicodemus Hello

- ^ John 19:34.

- ^ a b Baring-Gould, The Lives of the Saints, vol. III (Edinburgh) 1914, sub "March 15: S[aint] Longinus M[artyr]"; Baring-Gould adds, "The Greek Acts pretend to be by S. Hesychius (March 28th), but are an impudent forgery of late date." (on-line text).

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D, and Zlatko Pleše. The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 523

- ^ See at Kontos; "The name cannot be ascribed to any tradition; its obvious derivation from logchē (λόγχη), spear or lance, shows that it was, like that of Saint Veronica, fashioned to suit the event," noted Elizabeth Jameson, The History of Our Lord as Exemplified in Works of Art 1872:160.

- ^ Sticca, Sandro (1970). The Latin Passion Play: Its Origins and Development. State University of New York. p. 159. ISBN 978-0873950459. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

Longinus Jesus Christ blind.

- ^ Ruth House Webber (1995). "Jimena's Prayer in the Cantor de Mio Cid and the French Epic Prayer". In Caspi, Michael (ed.). Oral Tradition and Hispanic Literature: Essays in Honor of Samuel G. Armistead. Routledge. p. 633. ISBN 978-0815320623. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Godwin, Malcolm (1994). The Holy Grail: Its Origins, Secrets & Meaning Revealed. Viking Penguin. p. 51. ISBN 0-670-85128-0.

- ^ Nechvátal, Bořivoj (2001). "Dva raně středověké sarkofágy z Vyšehradu". Archaeologia Historica (in Czech). 26 (1). Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University: 345-358. ISSN 0231-5823.

- ^ "Hierosolymae, commemoratio sancti Longini, qui miles colitur latus Domini cruci affixi lancea aperiens" – Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7), Die 16 octobris

- ^ Calendar of Saints (Armenian Apostolic Church)

- ^ Vojvoda, Rozana (2008). Fragmenti svetačkih života pisani beneventanom i vezani za Dubrovnik. III. Kongres hrvatskih povjesničara (in Croatian). Supetar, Split.

- ^ Bulić, Goran (2011). "Konzervatorsko-restauratorski radovi na slici sv. Gaudencije i sv. Longin iz župne crkve sv. Antuna Opata Pustinjaka u Velom Lošinju". Godišnjak zaštite spomenika kulture Hrvatske (in Croatian). 35 (35): 233-240. ISSN 2459-668X.

- ^ Majer Jurišić, Krasanka (2011). "Zašto razgovarati o zaštiti spomenika?". Kvartal: Kronika Povijesti Umjetnosti U Hrvatskoj (in Croatian). 8 (1–2): 67–69.

- ^ "São Longuinho e a tradição dos 3 pulinhos". Aleteia. 2018-03-15. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31.

Diz-se que ele era um homem baixinho e que, servindo na corte de Roma, vivia nas festas. Nesses ambientes, por sua pequena estatura, conseguia ver o que se passava por baixo das mesas e sempre encontrava pertences de pessoas. Os objetos achados eram devolvidos aos seus donos. Assim, teria surgido o costume de pedir-lhe ajuda para encontrar o que se perdeu.

- ^ "São Longuinho e a tradição dos 3 pulinhos". Aleteia. 2018-03-15. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31.

Diz-se também que essa forma de agradecimento seria pelo fato de o soldado ser manco. Outra explicação afirma que os pulinhos remetem à Santíssima Trindade.

- ^ Xavier, Francisco Cândido (1938). "D. PEDRO II" (PDF). Brasil, Coração do Mundo, Pátria do Evangelho (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazil: Federação Espírita Brasileira. ISBN 978-8573287967. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-31.

Foi assim que Longinus preparou a sua volta à Terra, depois de outras existências tecidas de abnegações edificantes em favor da humanidade, e, no dia 2 de dezembro de 1825, no Rio de Janeiro, nascia de D. Leopoldina, a virtuosa esposa de D. Pedro, aquele que seria no Brasil o grande imperador e que, na expressão dos seus próprios adversários, seria o maior de todos os republicanos de sua pátria.