Woodie Flowers

Woodie Flowers | |

|---|---|

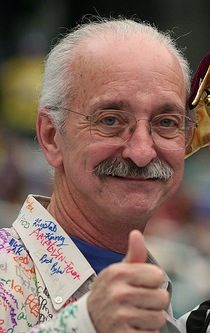

Flowers gives his signature thumbs up at the 2006 FIRST Championship in Atlanta, Georgia | |

| Born | Woodie Claude Flowers November 18, 1943 Jena, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | October 11, 2019 (aged 75) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Louisiana Tech University (B.S., 1966) MIT (M.S., 1968), M.E. (1971), Ph.D. (1973) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mechanical engineering |

| Institutions | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Doctoral students | Li Shu |

Woodie Claude Flowers (November 18, 1943 – October 11, 2019) was a professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His specialty areas were engineering design and product development; he held the Pappalardo Professorship and was a MacVicar Faculty Fellow.[1][2]

Flowers was known for co-creating FIRST, a youth organization known primarily for operating FIRST Robotics Competition and other student engineering competitions. Working with inventor Dean Kamen, Flowers helped design the organization's competition structure based loosely around his 2.70 class at MIT.[2]

Early life[edit]

Flowers was born in Jena, Louisiana on November 18, 1943,[3][4] and named after his grandfathers Woodie and Claude.[5] His father, Abe Flowers, was a welder and inventor; his mother, Bertie Graham, was an elementary-school and special education teacher.[6] Flowers had a sister, Kay.[4] As a boy, he showed mechanical aptitude like his father, Abe, and he earned the rank of Eagle Scout.[3] When he was seventeen, he and four friends were driving on Louisiana Highway 127 when they were hit head-on by another vehicle that was traveling at about 100 miles per hour (160 km/h). The collision killed two people in Flowers' vehicle and one in the other. The event ingrained his self-described "genetic opposition to violence" and his "fierce, vocal loathing of any spectacle that involves crashing pieces of machinery into each other with deliberate force."[7]

Career[edit]

1961–1973: Education[edit]

Flowers initially expected not to attend college, but at the advice of a high school teacher he attended Louisiana Polytechnic Institute under a disability scholarship,[4] graduating with a Bachelor of Science in 1966.[1][7] He then attended Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), earning his M.S. (1968), M.E. (1971), and PhD (1973) under the direction of Bob Mann.[1][8][7] His thesis, titled "A man-interactive simulator system for above-knee prosthetics studies," was on a robot-like prosthetic knee inspired by Mann's Boston Arm.[9][10][a]

1974–1987: MIT Professor[edit]

After receiving his doctorate, Flowers began as an assistant professor at MIT, working with Herb Richardson on the "Introduction to Design and Manufacturing" class.[10][8] Known by its course number as 2.70 (now 2.007), the class featured a design competition to build robotic mechanisms to accomplish a given challenge.[8][11] Flowers took over the class in 1974, developing it into one of the most popular classes at MIT.[8][12] He redesigned the challenge every year, always trying to make it more complex and exciting for students.[10] The competition was televised several years on the PBS show Discover: the World of Science.[13] The competition became akin to a sporting event, and was even jokingly referred to as MIT's true homecoming game.[14] In 1987, Flowers handed the class over to Harry West.[15]

Discover: the World of Science changed its name to Scientific American Frontiers in 1990, and Flowers served as its host[16] until 1993 when he was replaced by Alan Alda.[17]

1990–2019: FIRST[edit]

In 1990, Flowers began working with Dean Kamen on FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), a project to inspire a culture that celebrates science and technology.[18] Taking elements from 2.70, they created the FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) in 1992, which evolved into an international competition involving 3,647 teams and serving more than 91,000 students as of 2020.[19][20][21] Flowers introduced the phrase "gracious professionalism"[22] to FIRST, an idea which has since pervaded FIRST literature and culture.[23] Flowers served every year as National Advisor to FIRST.[24] He was active at FIRST events, working as an MC and being treated along with Kamen "like heroes."[23]

At the 2017 VEX Robotics World Championship, Woodie Flowers was inducted into the STEM Hall of Fame.[25]

FRC Woodie Flowers Award[edit]

In 1996, the FIRST Robotics Competition created the Woodie Flowers award, which was awarded to Flowers that year.[1] In years since, the award has served as a way for FRC teams to recognize distinguished adult mentors. At each FRC regional competition a Woodie Flowers Finalist Award (W.F.F.A) is presented to one nominee, qualifying them for the Championship Woodie Flowers Award (WFA) presented at the FIRST Championship.[26]

Later career[edit]

Flowers was a "Distinguished Partner" at Olin College, a member of the National Academy of Engineering, and a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[27] In 2007, he received a degree honoris causa from Chilean university Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello.[28]

Personal life[edit]

Flowers married Margaret Weas, who he met at Louisiana Tech University, in 1967. Flowers was known for having an eclectic selection of hobbies, including wildlife photography, scuba diving, unicycling, skydiving, and trapeze.[4]

Death[edit]

Flowers died on October 11, 2019, at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston following complications from aorta surgery.[29][4]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Woodie C. Flowers". MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Professor Emeritus Woodie Flowers dies at 75". MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Stone 2007, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d e Rufkin, Glenn (October 24, 2019). "Woodie Flowers, Who Made Science a Competitive Sport, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Cullinane, Maeve. "Afterhours with Woodie Flowers". The Tech. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Marquard, Brian (October 23, 2019). "Woodie Flowers, MIT robotics guru who championed 'gracious professionalism,' dies at 75 - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c Stone 2007, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d Chandler, David L. (May 7, 2012). "Woodie Flowers, a pioneer of hands-on engineering education". MIT News. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Flowers, Woodie Claude. "A man-interactive simulator system for above-knee prosthetics studies" (PDF). MIT. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c Stone 2007, p. 194.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Stone 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Stone 2007, p. 196.

- ^ "Woodie Flowers, on season 1". Scientific American Frontiers. Chedd-Angier Production Company. 1990–1991. PBS. Archived from the original on January 1, 2006.

- ^ Stone 2007, p. 197.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Cullinane, Maeve. "Afterhours with Woodie Flowers". The Tech. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "2020 Season Facts" (PDF). FIRST. January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Vision and Mission". FIRST. July 10, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Stone 2007, p. 207.

- ^ "Dr. Woodie Flowers". FIRST. July 27, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Dr. Woodie Flowers - STEM Hall of Fame Induction 2017. YouTube. VEX Robotics. May 15, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Submitted Awards". www.firstinspires.org. April 19, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- ^ "Woodie Flowers, Ph.D". Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Ceremonia Investidura Grado Honoris Causa Universidad Andrés Bello Dr. Woodie Flowers" (PDF). October 23, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "A Message about Dr. Woodie Flowers". FIRSTInspires. October 12, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

Works cited[edit]

- Stone, Brad (2007). Gearheads: The Turbulent Rise of Robotic Sports. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-8732-3.