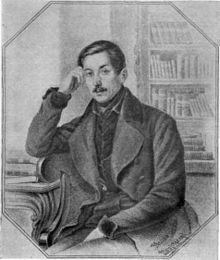

Serge Poltoratzky

Serge Poltoratzky (alternate spellings: Sergei or Sergey and Poltoratsky, Poltoratskii or Poltoratskiy), 1803-1884, was a Russian literary scholar, bibliophile and humanitarian. His major literary work was the Dictionary of Russian Authors, which he worked on for decades. He travelled extensively in Europe to find books and manuscripts needed for this work. He was also interested in the letters of Voltaire and in Franco-Russian cultural relations. He wrote articles for the French press on these and other literary topics, often under the pseudonym R.E. According to Yuri Druzhnikov, Poltoratzky was the first to introduce Pushkin's work to a western European audience, in the October 1821 issue of Revue encyclopedique (published in Paris).

Among Poltoratzky's literary friends were Victor Hugo, Nikolay Karamzin, Charles Forbes René de Montalembert, Alexander Pushkin, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve and Vasiliy Zhukovsky. He was also known for giving financial help to impoverished authors and scholars.

Poltoratzky's personal library, which included many rare books and unpublished manuscripts, was donated to the Imperial Public Library, now the Russian State Library.

Life[edit]

Serge Poltoratzky was the only son of Dimitry Poltoratzky and Anna Khlebnikova, who also had five daughters. Serge was primarily educated by tutors at the family home, Avchurino, on the east bank of the Oka River in Kaluga Province (Kaluzhskaya Oblast), but he also spent a year at the Richelieu Lyceum in Odessa. His parents were deeply interested in improving the material and social conditions of Russian serfs and peasants, and Serge inherited their commitment. In 1812 the family hid in Avchurino's attics as Napoleon’s army looted the estate during their retreat from Moscow.

Serge came into his inheritance at the age of 15, when his father died in 1818. At this time Serge was serving at court as a page to the Tsarina Elizaveta, wife of Tsar Alexander I. He later served in the Preobrazhensky Life Guards, according to his father’s and uncles’ wishes, but military life was not to his liking, and he soon resigned his commission, having reached only the lowly rank of praporshchik (often translated as “ensign”). Thereafter he devoted himself primarily to literary pursuits. Druzhnikov relates that after Poltoratzky's 1921 article, which mentioned Pushkin's poems Liberty and The Village and their criticism of Russian social conditions, appeared in France, he "was fired from his job and sent to live in the country under police supervision". This job may have been the Life Guards position, and the episode glossed for his children as a voluntary resignation.

Poltoratzky was one of the wealthiest men in Russia. He owned seven large estates, at least two houses in Moscow, and various smaller properties and investments. All this wealth had been accumulated in a mere two generations, as both his grandfathers were commoners ennobled to the rank of potomstvenniy dvorianin (hereditary untitled gentleman), Piotr Khlebnikov for service to Russian literature, and Mark Poltoratzky for his singing voice.

All Serge Poltoratzky's paternal uncles married into the titled nobility. His only aunt married Alexey Olenin, the first director of the Russian Imperial Library. His mother's brother emigrated to the US, and the family lost touch with him during the 1796-1801 reign of Tsar Pavel I, who banned all foreign correspondence.

Poltoratzky married in 1831, but within a few years his wife mysteriously disappeared, having been last seen leaving their Moscow house on foot. In 1843 he became engaged to Ellen Sarah Southee, 16 years his junior, and the daughter of an English gentleman farmer. She was related to poet Robert Southey. Later that year Poltoratzky's first wife was legally declared dead, his mother died, and his second marriage took place.

From 1843 Poltoratzky made his home at Avchurino when not engaged in literary travels. There he and his wife had three daughters and two sons, the eldest of whom died in infancy.

After the accession of the reform-minded Tsar Alexander II in 1855, many of the legal impediments to landowners’ freeing their serfs were removed. Poltoratzky took advantage of these changes to free his thousands of serfs between the years 1856 and 1859. In addition, he gave them land, livestock, tools and other goods to help them become self-supporting. He also advised the Tsar's Emancipation Committee, which was developing the terms of serf emancipation that would be enacted in 1861.

In 1859 Poltoratzky discovered that two of his estate managers had massively defrauded him. The men were tried and convicted, which might have enabled Poltoratzky to gain legal redress from the debts incurred on his behalf, but he did not pursue this possibility. Around the same time it became known to the imperial government that Poltoratzky's English wife had never converted to the Russian Orthodox church, and furthermore, that their children were being raised in the Anglican church. While this was perhaps technically legal, so soon after the Crimean War it was utterly unacceptable socially, and in imperial Russia, social-political favor would have been essential to the family's economic recovery. Poltoratzky liquidated his assets in Russia, paid off his debts, and prepared to emigrate to France, where he had some untouched funds.

In 1860 the Poltoratzky family left Russia for good. They went first to Charlottenburg, Prussia, where another son was born. They then proceeded to Paris, where Serge had long maintained a pied-à-terre for use on his literary trips. Thereafter the family divided their time between Paris and England, where the youngest son was born.

Death[edit]

Poltoratzky died in Neuilly, France in 1884.

Notable descendants[edit]

Serge Poltoratzky's literary legacy was continued by his daughter Frances Hermione de Poltoratzky (alternate spellings: Poltoratskaia or Poltoratskaya), 1850-1916. She wrote, primarily in French, novels, pamphlets on social and political issues, and works on Russian history.

The next generation's author was E. M. Almedingen, the daughter of Hermione's sister Olga. Almedingen wrote histories, memoirs, poems and novels for both adults and children. Her most successful works were several novelized children's biographies of her ancestors.

References[edit]

- Almedingen, E. M. Anna London: Oxford University Press, 1972

- Almedingen, E. M. Ellen New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970

- Almedingen, E. M. Fanny London: Oxford University Press, 1970

- Almedingen, E. M. A Very Far Country New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1958

- Druzhnikov, Yuri. Prisoner of Russia: Alexander Pushkin and the Political Uses of Nationalism New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 1999

- Hamst, Olphar. A Martyr to Bibliography: A Notice of the Life and Works of Joseph-Marie Querard, Bibliographer London: John Russell Smith, 1867