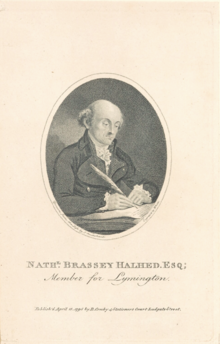

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 May 1751 |

| Died | 18 February 1830 |

| Occupation(s) | Orientalist and philologist |

| Spouse | Louisa Ribaut |

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed (25 May 1751 – 18 February 1830) (Bengali: হালেদ, romanized: "Haled") was an English Orientalist and philologist.[1]

Halhed was born at Westminster, and was educated at Harrow School, where he began a close friendship with Richard Brinsley Sheridan. While at Oxford he undertook oriental studies under the influence of William Jones. Accepting a writership in the service of the East India Company, he went out to India, and there, at the suggestion of Warren Hastings, translated the Hindu legal code from a Persian version of the original Sanskrit. This translation was published in 1776 as A Code of Gentoo Laws. In 1778 he published A Grammar of the Bengal Language, a Bengali grammar, to print which he set up the first Bengali press in India.[2]

In 1785 Halhed returned to England, and from 1790 to 1795 was member of parliament for Lymington, Hants. For some time he was a disciple of Richard Brothers, and a speech in parliament in defence of Brothers made it impossible for him to remain in the House of Commons, from which he resigned in 1795. He subsequently obtained a home appointment under the East India Company. He died in London on 18 February 1830.[2]

Early life[edit]

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed was born in a merchant family to William Halhed, a bank director, on 25 May 1751 and christened in St Peter le Poer, Old Broad Street; his mother was Frances Caswall, daughter of John Caswall, Member of Parliament for Leominster. He went to Harrow School from the age of seven to seventeen.[3]

Halhed entered Christ Church, Oxford on 13 July 1768, at the age of 17.[4] He remained there for three years but did not take a degree. William Jones had preceded him from Harrow to Oxford and they shared an intellectual relationship. At Oxford he learnt some Persian.[3]

Halhed's father was disappointed in him and decided to send him to India under the employment of the East India Company through his connections. His petition for a writership was granted by Harry Verelst. Appointed on 4 December 1771, Halhed was forewarned and had learned accounting.[5]

In India[edit]

Halhed was first placed in the accountant general's office under Lionel Darrell. He was next used as a Persian translator, and was sent to Kasimbazar for practical experience, and also to learn about the silk trade, by William Aldersey. It was in Kasimbazar that Halhed acquired Bengali, for dealing with the aurungs (weaving districts).[6] In Bengal he had several romantic interests: Elizabeth Pleydell, a certain Nancy, Diana Rochfort, and Henrietta Yorke.[7]

Halhed became one of Warren Hastings's favorites, and a believer in his approach to Indian affairs. On 5 July 1774 the Governor asked for an assistant for Persian documents, in addition to the munshis, and Halhed was appointed.

Marriage[edit]

After wooing several accomplished women, Halhed married (Helena) Louisa Ribaut, stepdaughter of Johannes Matthias Ross, the head of the Dutch factory at Kasimbazar when Halhed was stationed there. The betrothal probably took place in 1775.[8]

Association with Warren Hastings[edit]

When Hastings then nominated him for the post of Commissary General in October 1776, however, there was serious resistance, and Halhed found his position untenable.[9]

Leaving Bengal, Halhed went to Holland, and on to London. Financial reasons forced him to consider a return to India, but he tried to do so without overt support from Hastings. On 18 November 1783 he asked the company's directors to appoint him to the committee of Revenue in Calcutta. He was successful, but not in dissociating himself from Hastings. He returned to India as a reputed Englishman with a wife and black servant, but when he reached Calcutta, Hastings was in Lucknow.[10]

Halhed presented his credentials to Edward Wheler, the acting governor-general, but there was no vacancy in the committee and no other appointments could be made without Hastings. Then summoned by Hastings to Lucknow, he made a futile journey there, since Hastings had by then decided to leave for England and was bound for Calcutta.[11]

Hastings was planning to bring supporters to England, and wanted to have Halhed there as an agent of the Nawab Wazir of Oudh. At this point Halhed threw in his lot with Hastings.[11]

Support for Hastings and Brothers[edit]

Halhed therefore returned to England, on 18 June 1785, identified as a close supporter of Hastings. The political context was the rise in 1780–4 of the "Bengal Squad", so-called.[12]

The "Bengal Squad" was, in the first place, a group of Members of Parliament. They looked out for the interests of East India Company officials who had returned to Great Britain. From that position, they became defenders of the Company itself.[13] The group that followed Hastings to England consisted of: Halhed, David Anderson, Major William Sands, Colonel Sweeney Toone, Dr. Clement Francis, Captain Jonathan Scott, John Shore, Lieutenant Col. William Popham, and Sir John D'Oyly.[14] This group is called by Rosane Rocher the "Hastings squad" or "Bengal squad".[15] That follows the contemporary practice of identifying the "Squad" or "the East Indians" with the backers of Hastings.[12]

Edmund Burke brought 22 charges against Hastings in April 1786, and Halhed was in the middle of the defence. For the Benares charge, Halhed had drafted a reply for Scott, but it was not in accord with Hastings's chosen line. He also cast doubt on some of Hastings's account when he was called on to testify. As a result, Halhed became unpopular with the defence team.[16]

Halhed began to look for a parliamentary career: his choice of enemies made him a Tory. His first candidature, at Leicester in 1790, failed and cost him a great deal. He succeeded in acquiring a seat in May 1791 at the borough of Lymington, in Hampshire.[17] His life was changed in 1795 by Richard Brothers and his prophecies. A revealed knowledge of the Prophecies and Times appealed to Halhed and resonated with the style of antique Hindu texts.[18] He petitioned for Brothers in parliament when he was arrested for criminal lunacy. Unsuccessful, he damaged his own reputation.[19]

Life of seclusion and after[edit]

The turn of the century saw Halhed a recluse, as he was for 12 years in all. He wrote on orientalist topics, but published nothing. From 1804 he was a follower of Joanna Southcott. In poverty, he applied for one of the newly opened civil secretary posts at the East India company, and was appointed in 1809.[3]

With access to the Company Library, Halhed spent time in 1810 translating a collection of Tipu Sultan's dreams written in the prince's own hand. He also made translations of the Mahabharata as a personal study, fragmentary in nature, and made to "understand the grand scheme of the universe".[20]

The old "Hastings squad" had become marginal after the trial, but Hastings was called to testify as an expert on Indian affairs in 1813.[21] He died on 22 August 1818. Halhed wrote two poems, and was also given the responsibility of composing the epitaph.[22]

In spring 1819, Halhed declared his intention of resigning from the company's services after ten years of service. He was allowed a £500 salary, and recovered some of his early investments.[22]

Death[edit]

Halhed lived on for another decade, without publishing anything further. His quiet life came to an end on 18 February 1830. He was buried in the family tomb of Petersham Parish Church.[23] At his death his assets were estimated to be around £18,000. Louisa Halhed lived for a year longer and died on 24 July 1831.[24]

Legacy[edit]

Halhed's collection of Oriental manuscripts was purchased by the British Museum, and his unfinished translation of the Mahabharata went to the library of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.[2]

Works[edit]

Halhed's major works are those he produced in Bengal, in the period 1772 to 1778.[3]

A Code of Gentoo Laws[edit]

Just before Halhed was appointed as writer, the East India Company's court of directors notified the President and council at Fort William College of their decision to take over the local administration of civil justice: the implementation was left with the newly appointed Governor, Warren Hastings. Hastings assumed the governorship in April 1772 and by August submitted what was to become the Judicial Plan. It provided among other things that "all suits regarding the inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages, or institutions, the laws of the Koran with respect to Mohametans and those of the Shaster with respect to Gentoos shall be invariably adhered to." No British personnel could read Sanskrit, however.[25]

Translation was undertaken and 11 pundits were hired. Hastings envisaged making a text in English that contained the local laws. He intended to show the prudence of applying the Indian laws.

The pundits worked to compile a text from multiple sources, the Vivadarnavasetu (sea of litigations). It was translated to Persian, via a Bengali oral version by Zaid ud-Din 'Ali Rasa'i. Halhed then translated the Persian text into English, working with Hastings himself. The completed translation was available on 27 March 1775. The East India Company had it printed in London in 1776 as A Code of Gentoo Laws, or, Ordinations of the Pundits. This was an internal edition, distributed by the East India Company. A pirate edition was printed by Donaldson the following year, followed by a second edition in 1781; translations in French and German appeared by 1778.

The book made Halhed's reputation, but was controversial, given that the English translation was remote from its original. It failed to become the authoritative text of the Anglo-Indian judicial system. Its impact had more to do with Halhed's preface and the introduction to Sanskrit than the laws themselves. The Critical Review wrote in London, September 1777, that:[26]

"This is a most sublime performance ... we are persuaded that even this enlightened quarter of the globe cannot boast anything which soars so completely above the narrow, vulgar sphere of prejudice and priestcraft. The most amiable part of modern philosophy is hardly upon a level with the extensive charity, the comprehensive benevolence, of a few rude untutored Hindoo Bramins ... Mr. Halhed has rendered more real service to this country, to the world in general, by this performance, than ever flowed from all the wealth of all the nabobs by whom the country of these poor people has been plundered ... Wealth is not the only, nor the most valuable commodity, which Britain might import from India."

Halhed in the preface stated that he had been "astonished to find the similitude of Shanscrit words with those of Persian and Arabic, and even of Latin and Greek: and these not in technical and metaphorical terms, which the mutation of refined arts and improved manner might have occasionally introduced; but in the main ground-work of language, in monosyllables, in the names of numbers, and the appellations of such things as would be first discriminated as the immediate dawn of civilisation." This observation was shortly to be heralded as a major step towards the discovery of the Indo-European language family.

A Grammar of the Bengal Language[edit]

The East India Company lacked employees with good Bengali. Halhed proposed a Bengali translatorship to the Board of Trade, and set out a grammar of Bengali, the salaries of the pundits and the scribe who assisted him being paid by Hastings. Difficulty arose with a Bengali font. Charles Wilkins undertook it, the first Bengali press was set up at Hugli, and the work of creating the typeface was done by Panchanan Karmakar, under the supervision of Wilkins.[27]

The grammar was the property of the company, Wilkins informed the council on 13 November 1778 that the printing was completed, by which time Halhed had left Bengal. Halhed's Grammar was widely believed at the time to be the first grammar of Bengali, because the Portuguese work of Manuel da Assumpção, published in Lisbon in 1743, was largely forgotten.

Other works[edit]

Halhed's early collaboration with Richard Brinsley Sheridan was not an overall success, though they laboured on works including Crazy Tales and the farce Ixiom, later referred to as Jupiter, which was not performed. Halhed left for India. One work, The Love Epistles of Aristaenetus. Translated from the Greek into English Metre, written by Halhed, revised by Sheridan and published anonymously, did make a brief stir. The friendship came to an end, Elizabeth Linley chose Sheridan over Halhed, and later they were political enemies.

The opening of the Calcutta Theatre in November 1773 gave Halhed occasion to write prologues. A production of King Lear also spurred him to write more pieces. He produced humorous verse: A Lady's Farewell to Calcutta, was a lament for those who regretted staying in the mofussil.

Halhed wrote an anonymous tract in 1779 in defense of Hastings's policies with respect to the Maratha War. He began to write poetry, also, expressing his admiration for the governor, such as a Horatian ode of 1782. Under the pseudonym of "Detector" he wrote a series of open letters that appeared in newspapers, as separate pamphlets and in collections. These letters span over a year, from October 1782 to November 1783.

In the decade of Hastings's impeachment, Halhed remained involved in the war of pamphlets. The Upanisad (1787) was based on Dara Shikoh's Persian translation. He wrote and distributed a Testimony of the Authenticity of the Prophecies of Richard Brothers, and of his Mission to recall the Jews. Scandalously, he identified London with Babylon and Sodom: and was judged eccentric or mad.

See also[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Halhed, Nathaniel Brasssey". Biographical Dictionary of the Living Authors of Great Britain and Ireland. Printed for H. Colburn. 1816. p. 142.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d Rocher, Rosane. "Halhed, Nathaniel Brassey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11923. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ s:Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886/Halhed, Nathaniel Brassey

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 40–1. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 92–6. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ a b Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 121–2. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ a b C. H. Philips, The East India Company "Interest" and the English Government, 1783–4: (The Alexander Prize Essay), Transactions of the Royal Historical Society Vol. 20 (1937), pp. 83–101, at p. 90; Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society. DOI: 10.2307/3678594 JSTOR 3678594

- ^ Sykes, John. "Sykes, Sir Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64747. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 125–6. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 132–4. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 141–2. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 168–9. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ a b Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 226–7. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Fison, Vanessa (May 2015). "Nathaniel Halhed and his Descendants in Petersham in the Eighteenth Century". Richmond History: Journal of the Richmond Local History Society (36): 24–37.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Rosane Rocher (1983). Orientalism, Poetry, and the Millennium: The Checkered Life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751–1830. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 48 and 51. ISBN 978-0-8364-0870-6.

- ^ Dalrymple 2004, p. 40

- ^ Hossain, Ayub (2012). "Panchanan Karmakar". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

References[edit]

- Dalrymple, William (2004). White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200412-8..

External links[edit]

- Books by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed – archive.org

- Orientalism, poetry, and the millennium : the checkered life of Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, 1751-1830 by Rosane Rocher

- Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Halhed, Nathaniel Brassey". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Excerpts of his notes on some Persian translations of Sanskrit texts were published by Hindley under the title Antient Indian Literature Illustrative of the Researches of the Asiatick Society, established in Bengal. 1807.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Halhed, Nathaniel Brassey". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.